Great Game Redux

September 16, 2021 | Expert Insights

With the Taliban in supreme control of Kabul, the country has been given a new name - the Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, doing away with the “Republic” in the earlier title. This goes beyond mere semantics as it portends serious outcomes for the Afghan populace, as also for the surrounding region.

TALIBAN VERSION 2.0

The prominent faces that have been in the forefront for the top leadership of the reborn Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan comprise a mix of the old and the new. Foremost is 53 years-old Mullah Abdul Ghani Baradar, who was one of the four founders of the Taliban and was captured in Pakistan in 2010. Released in 2018 on American request, he headed the Taliban delegation in Doha during the talks leading to the U.S. exit. He is rumoured to be appointed the first Vice Emir once the Taliban formalises its government.

Next is Hibatullah Akhundzada, in the late 60s, who is the third supreme commander of the Taliban since 2016, when his predecessor fell victim to a drone strike. Reportedly close to the "Quetta Shura", he is likely to play a pivotal role in charting the rules governing civil society, especially those pertaining to women.

Another strong contender for the top slot would be Sirajudin Haqqani, who is relatively younger, being in his late 40s. He is the deputy leader of the Taliban and head of the Haqqani network. His network, deeply aligned with the Pakistani ISI, has been proscribed as a terrorist group by the U.S. As its leader, Sirajudin carries a US $ 5 million bounty, placed on his head by the U.S. State Department.

Finally, it is expected that Mullah Mohammad Yaqoob, son of the late Mullah Omar, the co-founder of the Taliban, would also find a place at the high table. Youngest at 30, he currently heads the powerful religious commission.

However, the Taliban is in no hurry to make a formal statement about the leadership, as they are still in negotiations to make the new government “inclusive”. According to Ambassador Shyam Saran, “There is certainly pressure in order to justify international legitimacy. There is pressure on the Taliban leaders from Pakistan, from China, from even Russia to try and make this, at least for appearance's sake, a somewhat more inclusive government by bringing in, perhaps, some of the other ethnic groups like the Tajiks, the Uzbeks, the Hazaras.”

GEOPOLITICAL BACKGAMMON

The triumphalism at the lightening outcome is patent amongst the well-known sponsors of Taliban, albeit somewhat subdued in consideration of the global horror at the return of the dreaded militants. It is understandable considering that Pakistan has invested 20 years of its political capital and has, in fact, provided tremendous material and military support to this movement against heavy odds. Having made this investment, obviously, it believes that the time has now come to reap some interest on this capital and that interest, from the Pakistani point of view, is only vis a vis India.

Pakistan has not much other concern. They will certainly want to see that the Indian presence in Afghanistan is as minimal as possible, if not completely absent. As for India, New Delhi will wait for the new dispensation in Kabul to fully crystalise before it makes its move. Much will depend upon the posture that this dispensation adopts with respect to India and what the shape of the government is.

Lt Gen PGS Pannu has reflected upon a deeper understanding between Pakistan and China, over the upheavals that are now taking place in South Asia. As per him, it was a rare coincidence that both the countries have made softer gestures towards India, to cool down tensions that had gripped the region as an outcome of increased hostility by Pakistan along the LoC and the massive build-up along India's northern borders in Ladakh by the PLA. The Pakistani Director General of Operations unilaterally offered an unconditional ceasefire all along the LoC in February, which obviously was accepted by India. Around the same time period, China agreed to a withdrawal and drawdown of forces, although not to the same extent as demanded by India. This cooling of tempers should have indicated that something big was brewing, going by India's past experiences with both these antagonists.

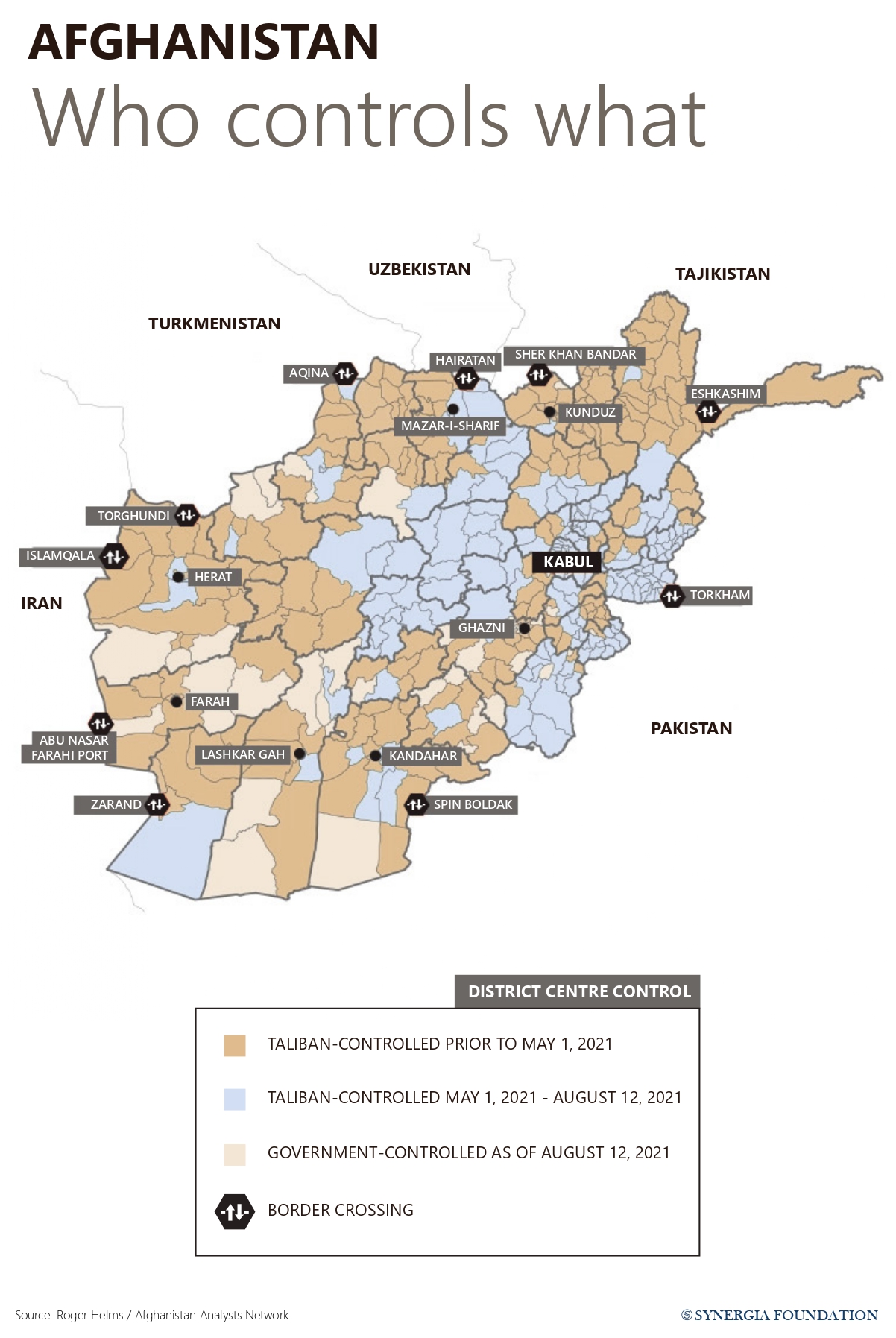

Going back in history, it must be recollected that the last time the Taliban had been on the threshold of seizing power, the Pakistani Army and the ISI were deeply involved in fighting with the Northern Alliance, with the 75 Independent Infantry Brigade of Pakistan completely embroiled in the assault on the strategic city of Mazar-i-Sharif.

Lt Gen PJS Pannu also summed up the strategic advantage now enjoyed by a collusive China, saying that “The Chinese actually now have got a ground route, clearly available to them during the summer season, because after February the routes would open up at some point and the CPEC corridor can be seen as a military corridor. The Hindukush passes also would be open now for Pakistan to do better business with Afghanistan.”

The AFPAK region has totally undergone a transformation with the departure of the U.S., the only external force that could act as a stabilising influence. Iran remains an unknown element, and the delicately balanced nations of Central Asia remain vulnerable.

Economics will force the Taliban to allow entry to extra-regional countries to put their money in Afghanistan. Of course, the Taliban would prefer China to do the heavy lifting on this account. Beijing has economic interests in Afghanistan, and while their military interests may not be so obvious, they would like the country to remain tranquil so that their investments are not jeopardised. More importantly, there is a genuine concern in China that Islamic fundamentalists could use the CPEC corridor to infiltrate into the restive Xinjiang province. China would be most unhappy if the Taliban genie that is now out of the bottle comes back to bite it.

However, as per Ambassador Shyam Saran, it would perhaps be wishful thinking to hope that the Pakistanis and the Chinese would embroil themselves in this ‘graveyard of the empires’. Amplifying this, he said, “I think the Chinese will certainly not want to repeat the mistakes that they think the United States has been guilty of. They will certainly want to see that their iron brother Pakistan is able to help them navigate a very complex geopolitical terrain in Afghanistan.”

What is now most worrisome is that the manner in which India deals with this crisis. The country had banked a great deal upon the Americans when they established themselves in Afghanistan, even though it was not a very easy transition to democracy. But with the U.S. gone, there is a clear and discernible void. A bolder China is bound to make inroads into this space, with Pakistan completely in its clutches. If Iran goes into their fold, along with Central Asia, then the situation will take a very serious turn for India.

With respect to China, at the end of the day, India is going to be facing China alone. It may receive some degree of support from the United States or other friends in terms of weaponry, technology and training. However, India must look beyond the U.S. to seek allies and partners, moving from mere transactions in military hardware to real military and strategic partnerships. Can the Quad mature in a manner that it becomes a reliable ally? The Japanese are too far from AFPAK, Australians have always gone very reluctantly into the Quad, and after Afghanistan, the American credibility is at its nadir.

THE BLOWBACK

As evident from the chatter on jihadi networks, the Taliban victory has been welcomed very gleefully. The humbling of the American "Crusaders” has given a huge psychological boost to terror groups around the world.

As per the Doha agreement, the Taliban would not have any truck with Al Qaeda and other such groups. However, U.S. intelligence has been reporting that these links still survive. Therefore, the principal objective of the peace agreement has not been met.

If Sirajuddin Haqqani is a part of the new government and the Haqqani group has an important role to play, then that would be a matter of deep concern because the Haqqani group is the closest to the Pakistan ISI. In fact, the two major attacks against the Indian embassy in Kabul were carried out by the Haqqani as agents, in a sense, of the Pakistani ISI.

Mike Mullen, in a deposition before the U.S. Congress, had said that the Haqqani group is a virtual arm of the ISI. Now, if there is going to be potential for that kind of a resurgence of cross-border terrorism, using Afghanistan as a base, naturally, this will be a matter of great concern to India.

The threat is both from land and sea frontiers, even if it is only an unconventional one. Gwadar, Djibouti and more worryingly, Chabahar could create a nautical nightmare for the Indian Navy to safeguard. The threat is not so much a direct one. It would most likely be a hybrid threat where technology has got a huge role to play, largely in the form of information/ influence operations. If that happens, then there won't be any alternative, but for India to use whatever means it has to make certain that that potential threaten does not actualise, especially when you have a still unresolved federal situation in Jammu and in Kashmir.

INDIAN STRATEGY

Even though the Taliban is a fully owned subsidiary of Pakistan, tactically engaging with the Taliban and whatever dispensation comes into power in Kabul is certainly something that would be worthwhile for India. As articulated by Ambassador Shyam Sharan “It is a question of waiting to see the true nature of the political dispensation. I think it is always good to engage. That is how you get to know what the calculations and intentions of the other side are. However, one should be under no illusion that the basic drivers of the Taliban policies have changed.”

The one great advantage that India has, is the substantial amount of goodwill gained amongst ordinary Afghans over the last 20 years. Therefore, it is important for India to keep its faith with the people of Afghanistan because they remain its greatest asset. They should not be treated as collateral damage. So, in practical terms, what does this entail? A large number of young Afghans, the post-Taliban Afghans who are studying in India, to whom the country has provided education and shelter should be supported going forward. It is important that India is large-hearted enough to reach out to them in their hour of need. It remains to be seen if India can provide that ray of hope to them without falling into the realpolitik syndrome.

Comments