A Golden Goose for the Exchequer

April 12, 2022 | Expert Insights

In the twenty-first century, data or information has become a key currency. Governments, corporations, and even smaller organisations are looking to cash in on the available data as demand grows exponentially.

Background

The Indian Ministry of Electronics and Information Technology (MEITY) has proposed a policy to allow the Central Government to monetise and sell public data to the private sector. The Ministry defended the policy by stating that the 2019 National Economic Survey allows the private sector to be granted partial access to data for commercial use. Since this clause already allows the private sector to reap profits from the available data, the government now wants to charge private corporations for accessing the same.

Analysis

In 2017, the Supreme Court of India had recognised the Right to Privacy as a fundamental right. However, over the past few years, as the digital way of daily life expands, much propelled by the pandemic, public data has become a veritable gold mine. We saw how Aadhar’s linkage with one’s bank account and phone number and a host of other transactions, despite concerns over database security, had generated a controversy in which finally the apex court had to intervene.

The MEITY, in their newest proposal, 'Draft India Data Accessibility and Use Policy, 2022', has openly advocated for the sale of public data. It aims to collect as well as use existing data, and process and tailor it for a required audience such as researchers, enterprises, and other government departments. This data will be known as a High Value Dataset (HVD). A background note to the proposal addresses some hurdles in data sharing, such as the lack of technical tools, the challenges in classifying and identifying HVDs and the absence of a body to monitor and enforce data sharing.

The Ministry is firm in its belief that the new policy would boost India’s efforts to reach the target of a five trillion-dollar economy, given the magnitude of data that can be harnessed. According to the Ministry, the project will be implemented by a newly established body known as the India Data Office (IDO), which will be under the MEITY. An additional Indian Data Council will also be formed for consultations. However, the nature of the Council, i.e., whether non-governmental consultants such as researchers and technical experts will be hired, has not been specified so far.

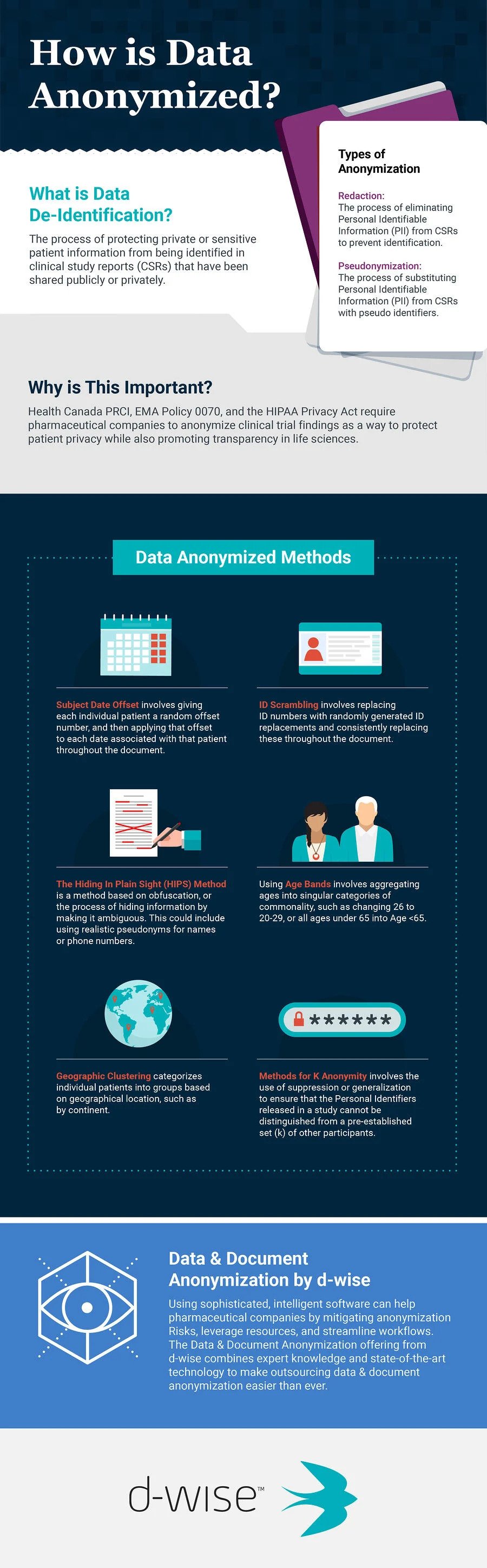

To address privacy concerns, the anonymisation of data has been recommended. The document also states that only high value data will be monetised, while minimal data will be available freely. Sensitive information, according to the proposal, along with remaining anonymous, will also have restricted access, as determined by the individual government ministries. Moreover, the government will possess a negative list of the dataset, which will not be shared or put up in the public domain.

Another issue that the proposal does not address is the role of the state governments. The draft allows for state governments to 'adopt portions of the policy.' It does not, however, mention whether data collected and collated by the states can be sold by the Centre. Should the Centre choose to do so, whether any percentage of the financial gains from this transaction will be given to the states has also not been addressed.

An important issue with the sale of public data for commercial use is that it may lead to surveys and census collation, not for public welfare but for-profit margins. This means that henceforth, more and more surveys will be conducted, collecting even the most minuscule information about the public. Ultimately, this information could lead to the enactment of more government as well as private policies which are not in the interests of the public.

In 2019, when the Personal Data Protection Bill was being discussed, data had been classified into two groups - personal data and non-personal data. Personal Data, along with containing basic information such as name, religion, age and address, had also contained sensitive information such as religious orientation, financial records, medical records etc. Non-Personal Data was essentially anonymised personal data. When the bill was being discussed, questions regarding why the government had so much data but was unwilling to share it was raised multiple times, especially given the anonymous nature of the data.

While the Draft India Data Accessibility proposal does not specify the use of non-personal data, it has referred to the use of anonymous data. The main problem with the policy is that there is no clause for legal redress should there be any breach of data protection. Moreover, the Data Protection Bill is yet to be passed in parliament. Therefore, without a legislative basis that strongly protects public data, the introduction of this policy can be seen as a hasty move.

Assessment

- The newly proposed Draft India Data Accessibility and Use Policy, 2022, has the potential to turn into a threat for citizens’ privacy, regardless of the anonymity feature. The draft trivialises the issue of privacy. It states that while the negative list of datasets will remain solely in public, much of the high-value data can be shared with private and other governmental bodies, if so deemed by the individual ministry. This could result in high value and sensitive data being sold to the highest bidder with a complete disregard for privacy and security.

- The draft also does not provide for legal recourse. The lack of a Data Protection Act can further add to the misuse of this proposed policy as there is no legal or legislative body that can be approached to hold the Ministry accountable, should there be a breach and misuse of citizens’ data.

- This proposal should ideally be drafted once the Data Protection Act has been passed, as the latter would provide legal guidelines for data sharing as well as data protection. The Data Protection Act must also have a provision whereby the buying and selling of data for commercial purposes can be monitored and regulated. This way, the government can strike a balance between public and financial interests.

Comments