Get the Chip Rolling!

August 4, 2021 | Expert Insights

Dr K.D Nayak is the former Director-General of the Defence Research and Development Organisation(DRDO). This article is based on his views at the 104th virtual forum on ‘Semiconductors and Supply Chains in Asia’, jointly organised by the Synergia Foundation and the STaiwan Centre for Security Studies.

As India explores avenues for collaborating with the Taiwanese semiconductor industry, it is important to map its strengths and weaknesses in this critical field.

At present, there are three fabrication units in the country. While the Semiconductor Complex Limited (SCL) in Chandigarh works on silicon technologies and application-specific integrated chips (ASIC), the Silicon Technology and Applied Research Centre (STAR-C) in Bangalore houses fabrication facilities for micro electromechanical systems (MEMS). Meanwhile, the Gallium Arsenide Enabling Technology Centre (GATEC) in Hyderabad focuses on compound semiconductor devices as well as related technologies and research.

However, these facilities mainly cater to the requirements of the Indian Space Research Organisation (ISRO) and the Defence Research Development Organisation (DRDO). There is no state-of-the-art fab for high-end, commercial semiconductors. As a result, successive Indian governments have been attempting to incentivise companies into setting up fab units within the country.

A SWOT ANALYSIS

Over the past seventy years, electronics has functioned as the oil for industrial revolutions around the world. Its omnipotence has made it possible for industries and countries to grow exponentially. There are two key components to this field, namely hardware (Nar) and software (Nari).

As far as India is concerned, it has progressed well in the area of software, despite lacking core design. In hardware components and assembly, however, the country’s contribution has been extremely sub-critical. This is particularly true for the semiconductor industry. Unless India becomes self-sufficient in this sector, it will not be able to grow and make commercial gains.

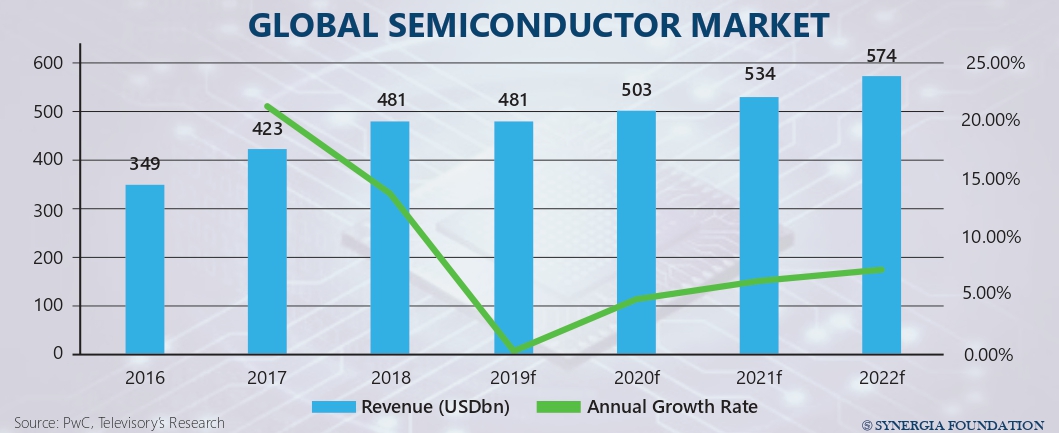

Currently, India has a good ecosystem for chip design. Most multinational corporations like Intel, IBM etc., have their design houses here. In fact, the backend for the first 65nm chip was done in the country. Apart from such obvious advantages in Very Large-Scale Integration (VLSI) design, India is one of the fastest-growing internet economies. With more than 65 per cent of its population below the age of 35, the country has a digitally aspiring demography. This translates to a robust demand for semiconductors in India, with the market being valued at $410 billion by 2030.

In terms of manufacturing capacity, however, the Indian semiconductor industry has fallen behind. Apart from limitations in hardware and equipment maintenance, it has suffered from the intermittent availability of land, power, water etc. However, many of these concerns have now been addressed, with at least five sites readily available for manufacturing.

The government has also embraced proactive policies to attract fab units. For instance, it has announced a one-billion-dollar cash incentive for chip manufacturers that are willing to shift to India.

THE ROAD AHEAD

To foster manufacturing in semiconductor components, there are two streams that India needs to focus on – a) silicon-based technologies, which constitute about 80%-90% of the semiconductors manufactured today, and b) evolving compound semiconductor technologies like Gallium Arsenide, Gallium Nitride, Silicon Carbide etc.

In the Silicon segment, India can concentrate on the establishment of fabs that manufacture state-of-art nodes in the 14nm-28 nm scale. Currently, the country only has older technology nodes that cater to strategic needs. Since disruptions in the global supply chain have created problems for industries like automotive, telecom and electronics-dependent data centres, there is a pressing need to scale up hardware requirements. India should build a good ecosystem through governmental incentives and investments, as was done in the initial phase of its software industry development.

TAIWAN AS A PARTNER

Taipei can be a critical partner for New Delhi, given its strength in the semiconductor manufacturing industry. After all, the Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company (TSMC) alone accounts for nearly 56 per cent of the global market in semiconductors. It is also the pioneer in high-end technology fabs that manufacture 3nm chips.

Against this backdrop, there is a unique opportunity for India to combine its design capabilities with Taiwan’s technological prowess. As a tentative first step, the two countries can consider cooperating on 14-28nm chips. Another area for potential collaboration could be the setting up of Assembly, Testing, Marking, and Packaging (ATMP) businesses in India. Since there are many micro, small and medium enterprises in Taiwan that are engaged in the ATMP sector, it is important to ascertain whether they can contribute to the Indian semiconductor industry.

As far as leveraging India’s design capacity is concerned, the key question is whether companies like TSMC or United Microelectronics Corporation (UMC) are willing to share their standard cell libraries with Indian start-ups. If they are, the fabrication of Indian designs can be undertaken in countries like Taiwan or Singapore. It is not necessary that the manufacturing is immediately shifted to India.

At a time when the semiconductor supply chain has been constrained by geopolitical risks, this is an opportune time for the two friendly nations to explore models of cooperation.

Comments