Gene editing: A possibility?

July 18, 2018 | Expert Insights

The Nuffield Council on Bioethics said changing the DNA of a human embryo could be ‘morally permissible’ if certain conditions are met.

However, gene editing remains highly controversial for a host of safety, ethical and religious reasons.

Background

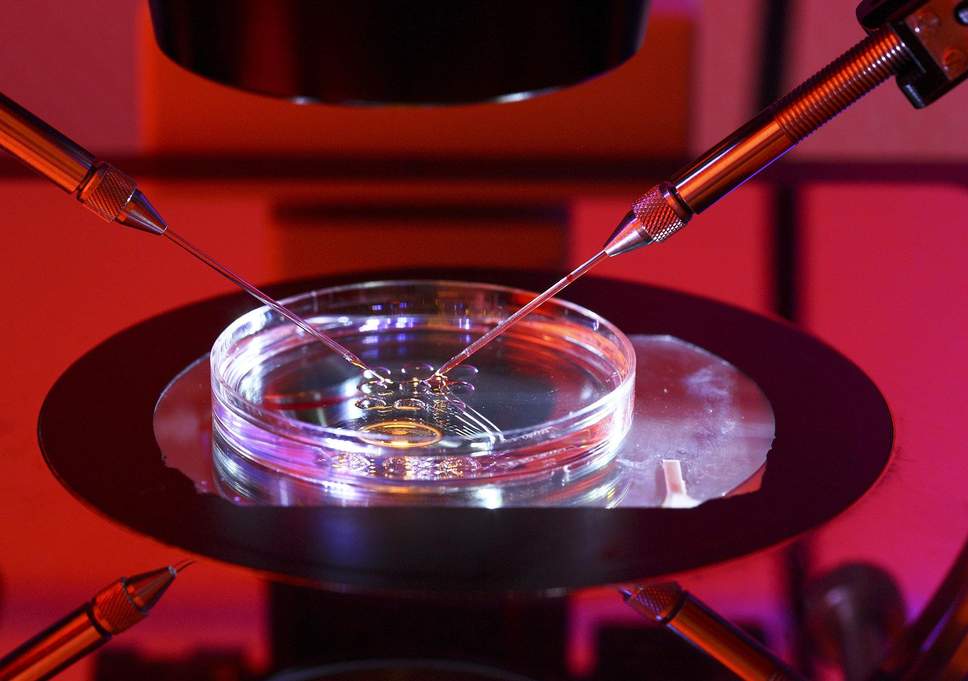

Genome editing is the process of editing an organism's DNA by altering, removing or adding nucleotides to the genome. This type of genetic engineering is useful for a number of applications, including targeted gene mutations, chromosomal rearrangement, and the creation of transgenic animals.

The first engineered nuclease technology, Zinc Finger, was presented in a 1991 publication by Pavletich and Pabo in the journal Science. Zinc Finger was the predominant genome targeting technology for over ten years, but over time drawbacks to the system emerged.

In 2009 when the genome targeting abilities of TAL effectors was published, they were quickly harnessed for genome editing and transcription activator-like effector nuclease, or TALEN, emerged. TALEN allowed for a larger window of potential target sites and a simple method of building TAL effector arrays was introduced in 2011.

In 2012 clustered regularly interspaced short palindromic repeats, or CRISPR, was demonstrated as a new genome editing tool. A mutation in a gene that causes disease can be repaired using CRISPR. This has increased the prospects of fighting inherited diseases and cancer among the medical community. However, the scepticism surrounding the ethical and moral aspects of genome editing continue to act as speed breakers for innovation to manifest from the field.

Analysis

The Nuffield Council on Bioethics, a leading UK ethics body, said that changing the DNA of a human embryo could be “morally permissible” if it was in the future child’s interests and did not add to the kinds of inequalities that already divide society.

The report does not call for a change in UK law to permit genetically altered babies, but instead urges research into the safety and effectiveness of the approach, its societal impact, and a widespread debate of its implications. In the event that the law is changed, gene editing of human embryos should be considered on a case-by-case basis by the fertility regulator, the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Authority, the report adds.

While laws in the UK and some other countries currently ban the creation of genetically altered babies, a handful of experiments around the world have shown that DNA editing could, in principle, prevent children from inheriting serious diseases caused by faulty genes. Karen Yeung, chair of the Nuffield working group said that there is no reason to rule out genome editing in principle.

DNA editing also raises the possibility of “designer babies”, where the genetic code of embryos created through standard IVF is rewritten so that children have traits the parents find desirable. The Nuffield report does not rule out any specific uses of genome editing, but says that to be ethical, any applications must follow the principles of being in the child’s interests, and have no ill-effects for society. George Church, a geneticist at Harvard University who was not involved in the report, said he agreed with the report’s guiding principle that gene editing “should not be expected to increase disadvantage, discrimination, or division in society,” adding that this would be aided by lower costs and better public dialogue and education. Making changes to common gene variants in sperm and eggs could save roughly 5% of babies from painful diseases, he said.

Counterpoint

The prospect of modifying genes in human embryos has long been controversial though. For a start, the procedure has yet to be proven safe. In a study published in Nature Biotechnology on Monday, British researchers found that the most popular tool for genome editing, Crispr-Cas9, caused more damage to DNA than previously thought. If the scientists are right, gene editing could disrupt healthy genes when it is meant only to fix faulty ones.

Marcy Darnovsky at the Center for Genetics and Society in California said,“They dispense with the usual pretence that this could – or, in their estimation, should – be prevented. They acknowledge that this may worsen inequality and social division, but don’t believe that should stand in the way. In practical terms, they have thrown down a red carpet for unrestricted use of inheritable genetic engineering, and a gilded age in which some are treated as genetic ‘haves’ and the rest of us as ‘have-nots’.”

Assessment

Our assessment is that if the law were to be changed to allow gene editing of human embryos there could be unintended consequences. Although technology could potentially reduce the number of people affected by certain genetic disorders, it could shake up the genetic makeup of our society as these changes are carried forward by the future generation. We feel that the NCB report, in not restricting the purpose of gene editing, has given scope for a lot of futuristic societal problems.

Comments