French President admits to use of torture in Algeria war

September 15, 2018 | Expert Insights

President Macron formally acknowledged its military’s systemic use of torture in the Algerian War of Independence in the 1950s and 1960s, a step forward in grappling with its colonial legacy.

Background

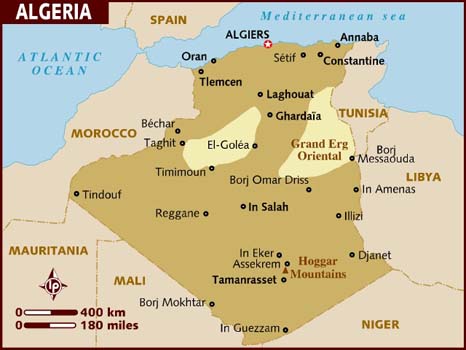

Algeria is the tenth-largest country in the world, and the largest in Africa with a population of 42 million people.

Conquered by France in 1837, Algeria was a colony but was integrated as a vital part of the country. By the 1950s, it was home to millions of French settlers, and when France was forced to give up overseas possessions in West Africa and Southeast Asia, it always held on tightly to Algeria.

Algeria achieved independence from France in 1962 after a four-year war which was characterised by assassinations, gross human rights violations and unchecked brutality on both sides.

Macron, 40, is the first French president born after the war and has shown a rare willingness to wade into the memory of Algeria, arguably the most sensitive chapter in the French experience of the 20th century and one that has had a profound influence on the country’s political institutions.

Analysis

President Emmanuel Macron issued a statement in the context of a call for clarity about the fate of Maurice Audin, a 25-year-old mathematician and anti-colonial activist who was tortured by the French army and forcibly disappeared in 1957, during Algeria’s bloody struggle for independence from France.

Audin’s death is a specific case, but it represents a cruel system put in place at the state level, the Elysee Palace said. “His disappearance was made possible by a system that . . . allowed law enforcement to arrest, detain and question any ‘suspect’ for the purpose of a more effective fight against the opponent,” read Macron’s statement.

In addition to recognising state-authorized torture, Macron called for the opening of archives concerning those who disappeared, such as Audin.

Macron’s recognition represented a move away from the “silence of the father” stance that has characterised France’s relationship to its colonial past for decades.

Macron’s statement drew hopeful comparisons to the last time a French president publicly atoned for the sins of the past — Jacques Chirac. President Chirac’s made a public apology in 1995 for France’s collaboration in the Holocaust, specifically in facilitating roundups of its own citizens who were then handed over to the Nazis.

Although the French president has drawn attention to colonial crimes that occurred in Algeria, there is still a reluctance to confront the violence that occurred in France itself. This include violent acts such as the brutal massacre by French police of pro-independence Algerian protesters in Paris in October 1961.

Interestingly, France’s current system of government came into being in 1958, in response to an attempted coup by French generals in Algiers. President Macron has hardly shied away from using these colonial-era executive powers, and at times he has relied on security provisions that stem from Algeria, notably the “state of emergency” put in place after recent terrorist attacks.

Counterpoint

It is plausible President Macron’s latest decree is an eye-wash to appease rising criticism of France neo-colonialism in Africa today. Despite de-colonising Africa decades ago, France still retains an enormous amount of influence over Francophone African countries.

The CFA franc – originally the French African Colonial franc – was officially created on 26 December 1945 by a decree of General de Gaulle. It is a colonial currency, born of France’s need to foster economic integration among the colonies under its administration, and thus control their resources, economic structures and political systems.

The CFA franc has three main pillars: Firstly, a fixed rate of exchange with the euro (and previously the French franc) set at 1 euro = 655.957 CFA francs. Secondly, a French guarantee of the unlimited convertibility of CFA francs into euros. Thirdly, a centralisation of foreign exchange reserves.

Since 2005, the two central banks – the Central Bank of West African States (BCEAO) and the Bank of Central African States (BEAC) – have been required to deposit 50 per cent of their foreign exchange reserves in a special French Treasury ‘operating account’. Immediately following independence, this figure stood at 100 per cent (and from 1973 to 2005, at 65 per cent).

Assessment

Our assessment is that Macron’s admission of the use of torture is the first of many required steps in the complete decolonisation process in Africa. The former Colonial powers have a complex relationship with their former colonies and the only way to bridge the gap is by acknowledging the crimes of the past. We believe that we can expect more statements and promises from Macron regarding the returning of cultural heritage articles from French museums to their country of origin. We also feel that this should be an ongoing process, not a one-time comment on such issues.

Comments