FOOD FOR THOUGHT

October 29, 2022 | Expert Insights

Ending world hunger has been one of the biggest collective goals of the planet for a long time, and undeniably there have been some remarkable successes, at least in Asia. But in recent years, the gravity of the global food situation only seems to have increased, especially in sub–Saharan Africa, bedevilled with conflict and climate change-triggered weather events.

Background

The United Nations World Food Programme (WFP) estimates that as many as 828 million people go to bed hungry every night, and the number of those facing acute food insecurity has soared - from 135 million to 345 million - since 2019. A total of 50 million people in 45 countries are teetering on the edge of famine. Experts believe a combination of four main factors, climate, conflict, costs, and the Covid-19 pandemic, have exacerbated the situation.

One of the leading causes of the food crisis is climate change, which only seems to be worsening, impacting worldwide food production and availability. Climate change manifestations, such as droughts, earthquakes, floods, and other extreme weather events, threaten to squeeze the soil of whatever fertility that centuries of unscientific cultivation have left.

The emission of greenhouse gases is also inextricably linked to the ever-evolving food sector. According to some estimates, the food sector is responsible for more than a third of greenhouse gases worldwide, including all stages of food production- from production and packaging to consumption and waste management. The presence and number of malnourished people are generally higher in countries more prone to extreme climatic conditions.

Analysis

Developing countries are caught in a Catch-22 situation; in their efforts to increase agricultural surface area, they denuded savannahs and forest cover, leading to global warming and triggering catastrophic climatic mega-events. As per estimates, around 80 per cent of all forests are being cleared globally to make room for farmland. For instance, the Amazon is losing trees at a startling rate to make way for soy fields. A joint statement by a coalition of organisations fighting against climate change and ending world hunger states, "If we are to achieve a world without hunger and malnutrition in all its forms by 2030, we must accelerate and scale up actions to strengthen the resilience and adaptive capacity of food systems and people's livelihoods in response to climate variability and extremes."

Small-scale farming traditionally supported peaceful and healthy communities. Because small farms primarily serve domestic and regional markets, they are particularly crucial in underdeveloped nations. The civic and social involvement, trust, and attachment to local cultures and communities are also higher in areas where small-scale farming is predominant. Small farms and other rural small and medium-sized businesses play a crucial role in the local economy by generating jobs and opportunities, which lessens the need for migration and, thereby, conflicts with neighbours.

Breaking the vicious cycle of hunger and conflict is the epicentre of the global hunger crisis. Hunger hotspots are usually conflicted zones where instability has further encouraged climate degradation practices. While these are clearly demarcated and well-known to international bodies, there is little salvation available as the funding is not there. Moreover, which NGO will risk everything to plunge into the conflict-riven space of such countries to work with local farmers displaced by conflict within their country? Only once the conflict situation has been managed other meaningful activities can be initiated. For instance, in Colombia, after the peace deal, increasing production and rural job options resulted from access to funding and training, discouraging young people from joining armed groups.

Global economic shocks find their reverberation in food insecurity. The people struggling to recover from the effects of Covid-19 restrictions were severely impacted by the unprecedented rise in global food prices in 2021 due to the war in Ukraine. With prices expected to remain high through the end of 2024, the war has changed global trade patterns, production, and consumption of commodities, worsening food shortages and inflation. Rising energy costs and transport methods have also affected global food supply chains.

As is often the case, the most vulnerable are hit the hardest: women, youth, indigenous peoples, and rural farmers as they struggle to gain access to training, finance, innovation, and technologies.

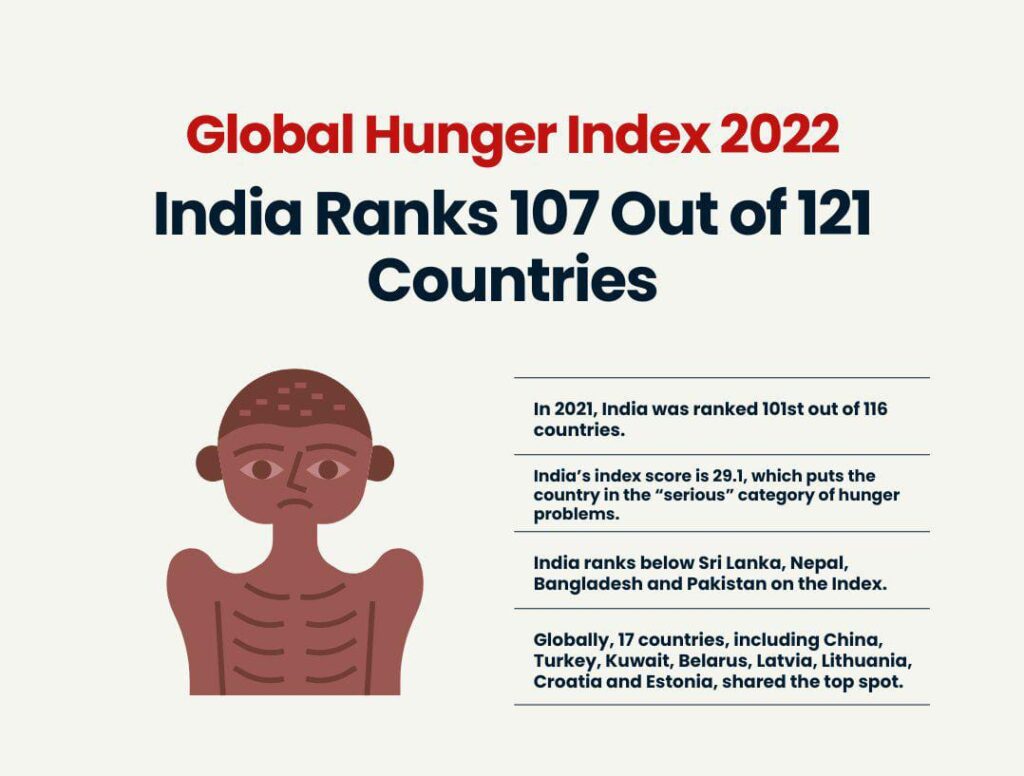

In the recent rankings published by Concern Worldwide and Welt Hunger Hilfe, India has been ranked 107th out of 121 countries in the Global Hunger Index with a score of 29.1, which puts it in the serious category. The Government of India released a statement in response to the ranking calling it an ‘erroneous measure of hunger and suffers from serious methodological issues', and ‘a consistent effort is yet again visible to taint India’s image as a Nation that does not fulfil the food security and nutritional requirements of its population. The government also said that it was ‘evident such questions do not search for facts based on relevant information about the delivery of nutritional support and assurance of food security by the Government.’

Assessment

- Technology will continue to be crucial in the battle against hunger and in meeting the demands of smallholder farmers. Farmers need to connect to the larger economy and financial institutions to boost output, agricultural sales, and financial management.

- Establishing connections between multi-stakeholders like Food Innovation Hubs, universities, NGOs, (local) governments, start-ups, mid-size and small-scale businesses, and venture capital is one way to promote national and regional innovation ecosystems rigorously. Another is reviewing regulations that impede the scaling up of agricultural innovation.

Comments