Factory Reset for Surveillance Tech

August 9, 2021 | Expert Insights

An international collaboration has unveiled a list of over 50,000 phone numbers that were potential surveillance targets for Israel-based Niv, Shalev, and Omri (NSO) group’s clients. The list includes journalists, human rights activists, lawyers, politicians, and security officials. This investigation calls for urgent restructuring of cybersecurity at domestic and international levels.

BACKGROUND

Israel has been known for developing high tech defense production systems since as early as the 1960s. Additional aid from the US over the years, totalling USD 146 billion, has made Israel one of the leading arms exporters in the world. From a domestic standpoint, Israel has become a hub for private data-mining organizations like AnyVision, Onavo, and NSO group. Strikingly, these companies have been linked to surveillance operations to monitor Palestinians. Their employees have also been tied to Israeli government entities and military intelligence units.

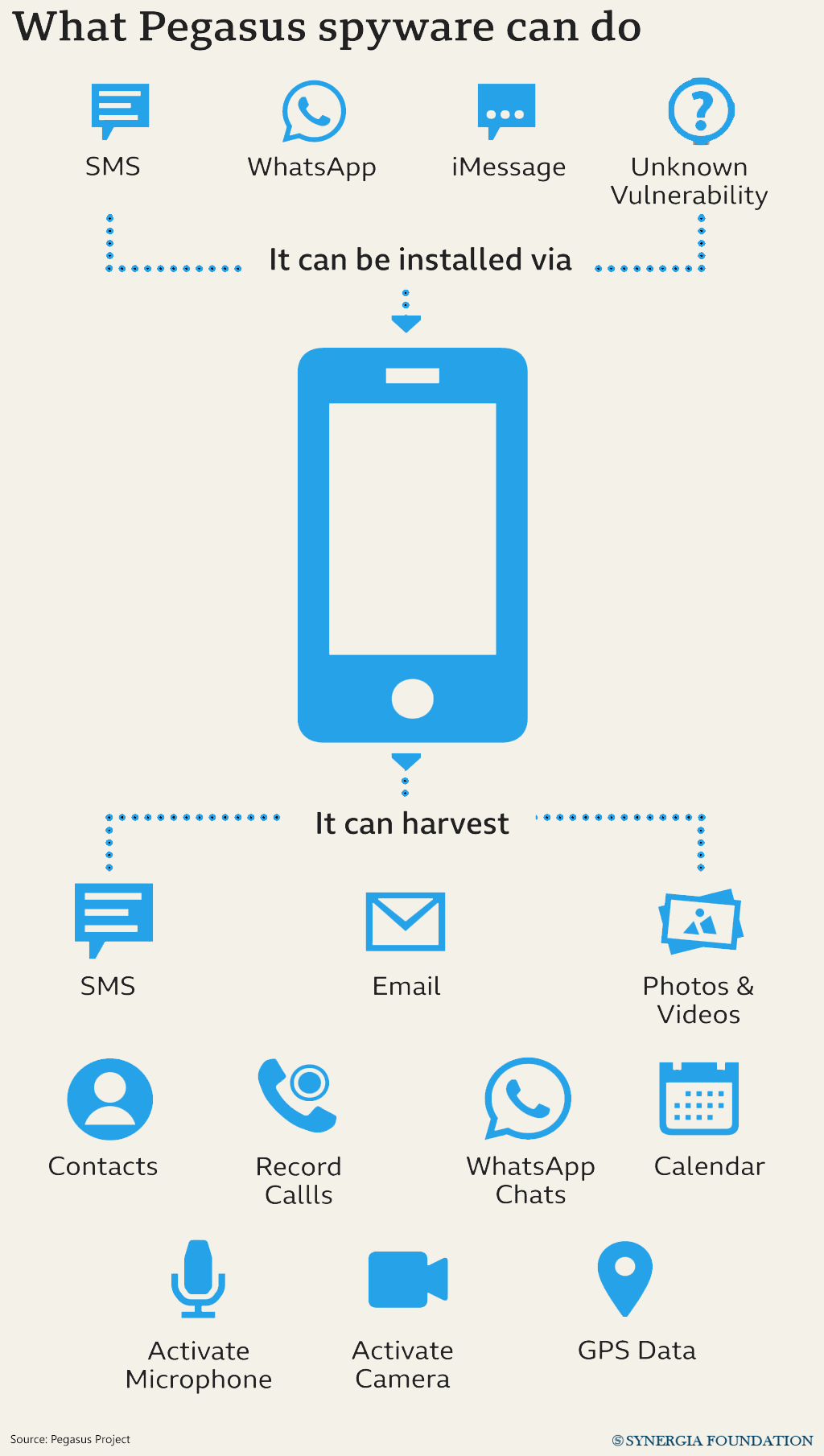

NSO group is the parent company of the Pegasus spyware used to hack into target smartphones. Established in 2010, the company gained credence for developing innovative technology for enabling remote access to phones for repairs. But by 2016, it had reportedly been used for illegally surveilling a United Arab Emirates human rights activist. Subsequently, a 2018 report from Canada-based Citizen Lab revealed the role of NSO’s Pegasus spyware in the murder of a Saudi journalist.

ANALYSIS

Tried and tested through its domestic cyber offensives, Israel’s military equipment has become favourable across the world. Its decision to export to countries such as Azerbaijan, Saudi Arabia, and UAE promotes its strategic interests by gaining allies for its proxy war against Iran. Maintaining security ties involves exchanging key intelligence that could inform Israel’s diplomatic decisions, enhance its global image, and reduce anti-Israel stances. This offers Israel high incentive to partner even with human rights violators and low rankers in the World Press Freedom Index. In fact, Israel’s cyber and military diplomacy precipitated its normalization deals with UAE and Morocco -- two of the NSO group’s likely clients.

The NSO controversy not only indicates an erosion of basic privacy, but also a broader, more troubling trend of authoritarian cyber-surveillance. Italy-based surveillance organization, Hacking Team, for instance, had its export license revoked in 2015 under similar grounds. The privatization of the cyber defense sector has ramped up competition for-profit and diplomatic goals. But if participating governments are unaccounted for and evasive about their surveillance practices, democracy will remain under threat.

COUNTERPOINT

Even after Whatsapp sued the NSO group in 2019 for conducting cyber espionage on civilians using its call feature, NSO denied all allegations and insisted on adherence to the UN Guiding Principles on Business and Human Rights. It preaches transparency and declares a rigorous vetting process through its Governance, Risk and Compliance Committee, but keeps its clients confidential. It claims to strictly limit its business to intelligence and law enforcement agencies across 40 countries. The company also claims to have suspended five clients over the last few years due to their unethical practices.

ASSESSMENT

- Individuals may take steps like regularly updating the device software, using VPNs, and resetting the phone for short-term relief. But this must be followed with rigorous monitoring from non-state actors and civil society. Citizens must demand judicial review and revise domestic laws around cybersecurity based on expert recommendations.

- Meanwhile, international law can ensure comprehensive checks and balances for cyber diplomacy, much like the United Nations Group of Government Experts’ rules on cybersecurity negotiations. Tech companies may develop a kill-switch for tools that transgress their authorized functions. Governments can also sanction or place moratoriums on unverified cyber-surveillance companies until they are fully investigated.

Comments