Drug Industry Eludes Pandemic

February 24, 2022 | Expert Insights

Very few segments of economic activity have managed to escape unscathed from the devastating impacts of the pandemic, crippled by a downward spiral of production glitches, demand swings, transportation issues and supply chain crisis. Despite this market mayhem, the poisonous tentacles of the illegal drug industry - production, trading and consumption - remain strangely aloof from the chaos.

Background

The illicit drug industry has not only survived the pandemic, but in many countries, has witnessed a surge after a few initial hiccups. Record drug seizures in key routes indicate a boom in production, fuelled by instability and a pandemic-induced crisis in the traditional industries employing millions.

The 2021 UN World Drug Report connects the increasing inequality, poverty and lack of opportunities for socio-economic development with the increased drug use and its production and trafficking. Says UNODC Executive Director Ghada Waly, “Rising unemployment and plummeting opportunities are expected to disproportionately affect the poorest, making them more vulnerable to drug use, trafficking and cultivation, to earn money to survive the global recession.”

Analysis

The COVID-19-induced economic and social disorder has apparently driven more people into the folds of drugs. The use of recreational drugs such as MDMA and cocaine, which fell during the initial lockdowns in 2020, has since bounced back. A significant increase in drug seizures in the recent past is indicative of enhanced production and distribution. Obviously, the illicit industry is upscaling production and supply to meet the increased demand and exploit the disruptions caused by the pandemic. The Spanish police recently made a historical seizure, unearthing over 2.5 tons of methamphetamine in a series of coordinated raids in various cities.

It only goes to underscore the adroitness and innovativeness of drug barons and their countless minions to surmount the disruptions of the pandemic. When international supply chains for essential chemicals faltered due to lockdowns, the drug industry developed its own precursor chemicals for synthetic drugs, thereby effectively bypassing international controls and logjams.

The marketing, too, has been in tune with the changing times of a world living under lockdown. Just like traditional online e-commerce businesses, they have resorted to striking deals online; some have even attempted novel delivery systems to reduce human contact, such as drones. Hidden in food containers, which are less vulnerable to disruption than electrical home appliances, these ‘online purchases’ found their ways undetected to their waiting customers.

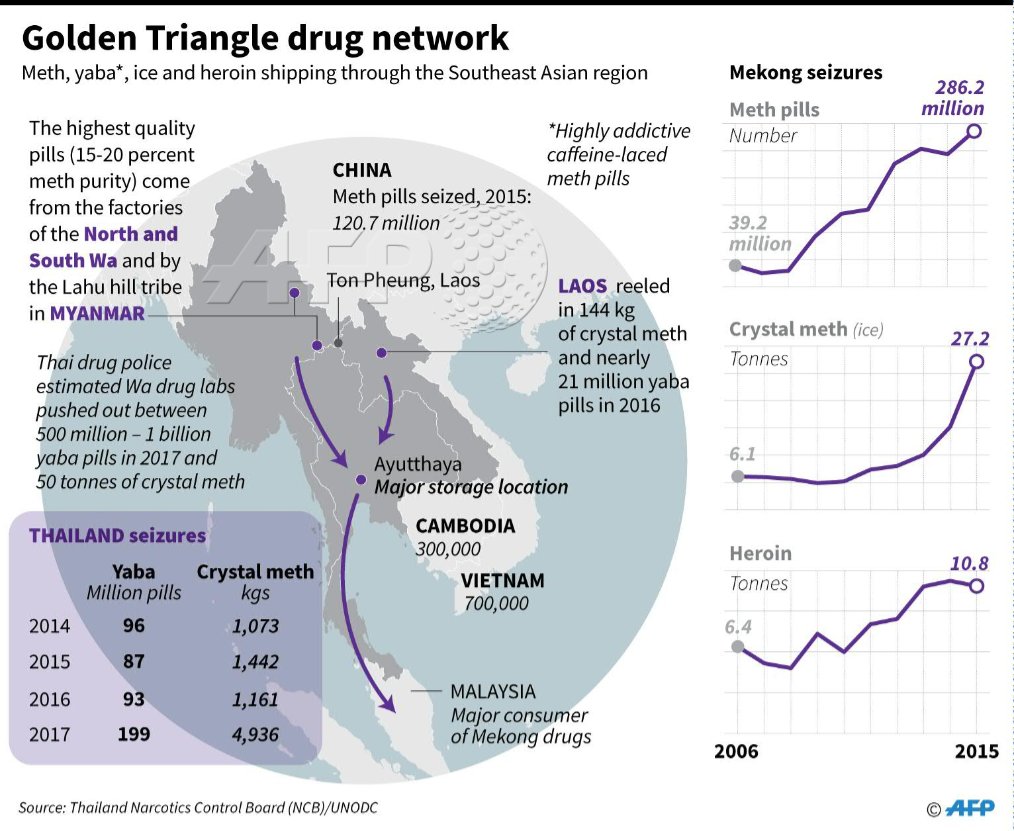

Key trafficking routes such as the Balkan Route for high-quality heroin consignments through Iran and Turkey to Europe is mostly conducted in vehicles and has not been seriously affected by the shipping crisis. The same is true for the meth trade in Southeast Asia, much of which happens overland between Lower Mekong countries.

The narcotics trade is propped up by political instability in major drug-producing countries. There is a close and direct linkage between conflict-ridden states and the production and trafficking of narcotics. In war-torn Syria, the government has reportedly played a supportive role through the alleged involvement of the ruling elites in the production and trafficking of Captagon. Apparently, the drug trade provides an easy avenue to bolster finances that are seriously strangled by sanctions and growing economic crises.

Meanwhile, Afghanistan has remained in the news for all the wrong reasons ever since the takeover by the Taliban. A vast quantity of Meth is being produced in the Afghan countryside using a local plant, Ephedra and has been flowing unimpeded into Iran and also to Africa via Pakistan and the Indian Ocean. According to recent research, the production of Ephedra appears to be increasing in Afghanistan as the country collapses into economic crisis after the exit of the Americans and freezing of national assets in foreign banks.

The global drug menace has three primary areas of drug production- the Colombian belt, the Afghan belt and the Golden Triangle in South-East Asia. Nowhere is the recent drug boom more pronounced than in the Golden Triangle, where Laos, Thailand and Myanmar intersect. In October, the police had grabbed 55 million methamphetamine tablets in Laos, Asia's largest-ever drug bust. Regional drug production and trafficking have intensified following the February coup in Myanmar, which plunged the country into chaos.

In Central America, Panama is the entry point for the South American drug production centres, much of which is destined for the United States. Panama seized a record haul of 128 tons of drugs in 2021. The figure represented a 43 per cent increase on the previous record of 90 tons from 2019. Despite being one of the hardest-hit economies from the pandemic, Latin America has seen the illegal drugs industry making immense profits during this period. These powerful drug cartels with strong international networks are getting stronger by the day and can impact the geopolitics of the region. In a recent poll conducted in Latin American countries, fighting drug trafficking has been listed as the single most important national security issue.

This Golden Crescent is the region comprising Afghanistan, Iran, and Pakistan. Recent turbulent political and economic conditions in Afghanistan have fuelled a sharp rise in opium production and trade in the country. As the drug trade booms under the Taliban, South Asian countries like India are most affected by the increased supply, especially its border states like Punjab, already heavily in the grips of a drug crisis.

International efforts thus far have largely only been able to displace, not eliminate, drug trafficking to other countries. Failures of these programmes, experts argue, have highlighted the need for a ‘focus on rehabilitation, the decriminalisation of currently illicit substances, and even the legalisation of all drugs.’ The war on drugs has generated a vicious cycle; successful counter drug campaigns create artificial shortages in the illicit drug market, leading to higher prices making drug production highly lucrative even at much greater risk. This has led to a spiralling of criminal organisations, many supported by rebel movements, that jump into the drug game.

Assessment

- Political and economic tensions clearly lay the foundations for the spread of drug trafficking. The fact that even the current pandemic has not made a dent in the industry speaks of its entrenched networks and widespread demand base. Greater cooperation worldwide is essential so that crime and violence related to drug abuse do not profit from COVID-19.

- Global efforts at limiting the spread of drugs have not met with huge success and have instead resulted in shifting the problem to other locations. In addition, an increase in violence and crimes demands a rethink of what might be a better approach to tackling this issue. It would be beneficial to undertake social and preventive approaches which could more effectively address this global menace.

Comments