In the Docks

October 19, 2021 | Expert Insights

In a mammoth global investigation that unearthed almost 12 million records of offshore service companies, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ) has exposed the shadowy financial dealings of the rich and the powerful. Dubbed as the ‘Pandora Papers’ leak, it reveals the extent to which incomes and assets are stashed away in tax havens by politicians, public officials, corporate executives, celebrities, and billionaires. Aiding them in this effort is an entire ecosystem of auditing companies, legal professionals and financial experts who create offshore structures and trusts to mask the beneficial owners of the property.

With the publication of this explosive report, the international community has been served yet another reminder about the need to promote financial transparency. Although many of the impugned transactions are not strictly illegal, they are still politically embarrassing for several public figures whose financial secrets have been revealed.

AN OLD AND SORDID SAGA

Stashing wealth in offshore tax havens has long been in practice, with lax rules and all-around complicity enabling the system to flourish unimpeded. Since 2013, however, this offshore services sector was rocked by a series of financial data leakages. From the 2016 Panama Papers case to the 2017 Paradise Papers leak (both initiated by the ICIJ), these events had shed light on the complex international tax avoidance schemes devised by offshore firms.

In fact, the former investigation had exposed a vast network of tax havens established by individuals from more than 200 countries, thereby triggering police raids and the enactment of new anti-money laundering laws within different jurisdictions. For its efforts in uncovering such tax sheltering schemes, the ICIJ had gone on to win the Pulitzer Prize. Similarly, the Paradise Papers were leaked a year later by the ICIJ after combing through the treasure troves of data in company registries hosted by secrecy jurisdictions.

This time around, the Pandora Papers investigation is believed to be much larger than the previous two leaks. More than 600 journalists in 117 countries have sifted through the data files of 14 firms in the offshore financial services industry to lay bare the hidden fortunes of some of the most influential people in the world.

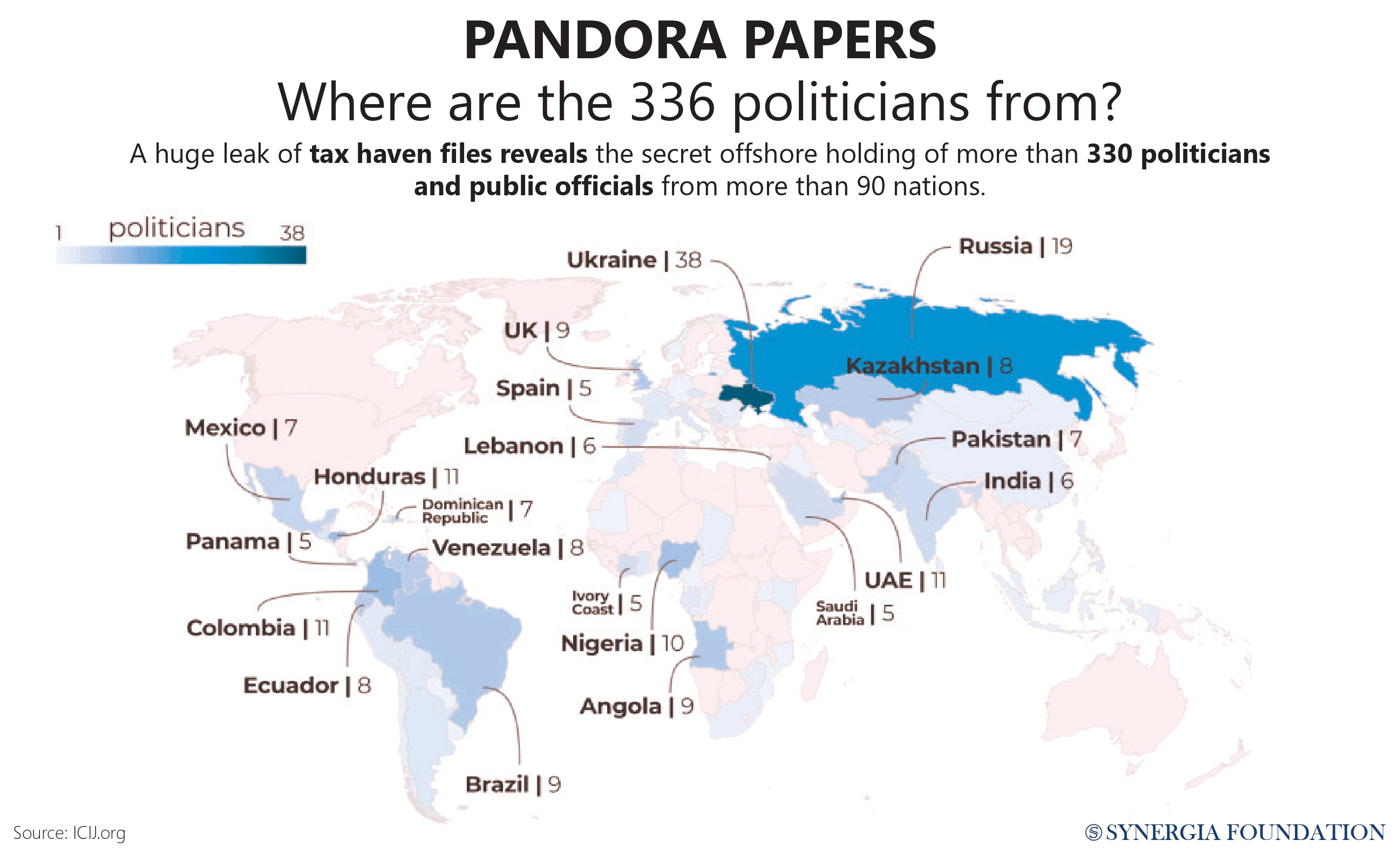

Reports indicate that the papers have provided incriminating information on more than 330 politicians and public officials from over 90 countries and territories. This includes the King of Jordan, the Presidents of Ukraine, Kenya and Ecuador, the Prime Minister of the Czech Republic, and a former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom. Persons within the inner circle of the incumbent Russian president and the Pakistani Prime Minister have also been named. As far as Indians are concerned, the secret documents have exposed the financial data of several key politicians, sportspersons, industrial leaders and other public figures.

ANATOMY OF TAX AVOIDANCE

The recent revelations by the ICIJ have served to underscore how wealthy individuals shield their income and assets from regulatory scrutiny. By setting up shell companies, trusts or holding firms in offshore jurisdictions and funnelling their money there, they keep their financial activities in the shadows. Specialist firms are paid to set up and run these shell companies in jurisdictions with lower taxes. Existing only on paper, such companies have no staff or office. Their operations are kept deliberately obscure as they have been created for the sole purpose of disguising ownership.

An analysis of the leaked documents indicates that more than two-thirds of paper companies are established in the British Virgin Islands, a popular destination for the thriving offshore system. Other preferred jurisdictions for hiding wealth include Panama, Switzerland, Seychelles, Belize, Delaware, Nevada, South Dakota, Monaco, Singapore, Hong Kong, Samoa and the Cayman Islands. According to the International Monetary Fund, the use of such tax havens has cost governments up to $600bn in lost taxes every year.

For the tax authorities, it is increasingly difficult to track the money that goes out of their jurisdictions, as the offshore firms employ a process called ‘layering’. This entails the movement of assets through multiple tax havens before parking them in a previously decided destination. Although such methods of ring-fencing wealth are not always illegal, they nevertheless violate the spirit of the law.

IN MURKY WATERS

In many countries, it is not necessarily unlawful to benefit from offshore entities. Many people have legitimate reasons for holding assets abroad. For example, offshore jurisdictions can be relied upon to safeguard income from criminal attacks or unstable governments in politically volatile regions. It can also serve as an effective method for mitigating extortion attempts.

Despite such benefits, the secrecy offered by offshore havens is an attractive loophole for tax evaders, drug traffickers, fraudsters, money launderers, kleptocrats and other unscrupulous elements. Given that several countries have no regulatory requirements to register the ultimate beneficial owners of the property, malicious actors can shroud themselves in layers of legal records. They are, in turn, assisted by a whole network of bankers, auditors and accountants who are aware of the gaps in the system.

Owing to the deployment of these complex mechanisms, it becomes difficult to identify how much of the wealth is tied to criminal enterprises or other unlawful activities. As a result, advocates of financial transparency call for greater regulation of the offshore services industry to curb corruption, money laundering, tax abuse and other financial crimes.

Assessment

- At a time when the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated income divides in urban and rural areas, the global penetration of secretive finance will not be viewed kindly by the general public. It will carry a political sting in several jurisdictions, with renewed attention being paid to the need to strengthen international financial regulations.

- More often than not, those who can put an end to ‘tax-haven shopping’ are often the very same people who benefit from it. As a result, it remains doubtful whether the continuous stream of illicit money can be effectively curbed. Additionally, the weak regulation of lawyers and other professionals who are protected by client privileges remains a pressing concern.

- Over the coming months, the Pandora Papers will accelerate the global shift to a minimum corporate tax, which seeks to prevent multinational companies from shifting profits to low-tax jurisdictions. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) has already announced that 136 countries will establish a 15 per cent minimum corporate rate from the beginning of 2023.

Comments