Declining Demographics

February 9, 2022 | Expert Insights

Over the past 50 years, most countries were preoccupied with the social and economic implications of spiralling birth rates. Now the focus seems to be drifting in the opposite direction, with low birth rates being looked at as a significant challenge and policymakers revisiting their demographic strategies.

Background

Recently, an editorial in a Chinese state-run paper advocated for all members of the Communist Party (CCP) to “personally carry out the nation's new three child policy” (which soon disappeared after a massive online backlash). While China’s concern with its declining birth rates is well recorded, especially in relation to the social consequences, a similar phenomenon is coming to the fore elsewhere too.

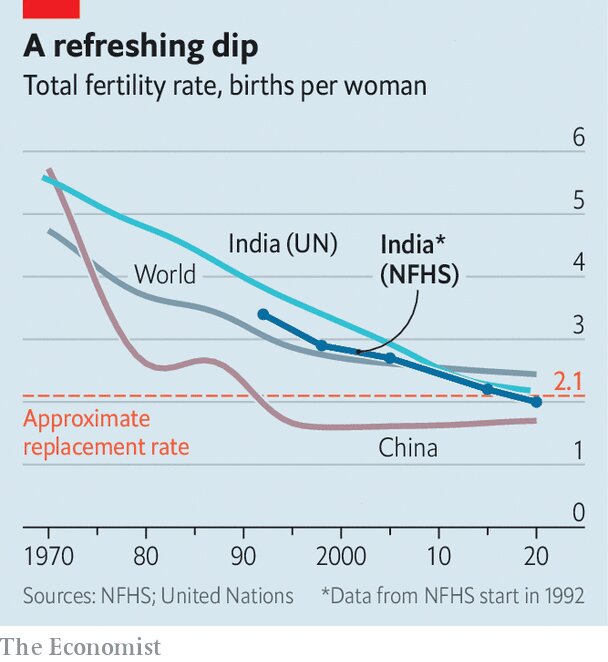

Between 1970 and 2020, the world population had increased by 4 billion while the global fertility rate dropped from 4.7 to 2.4. This indicates that the growth rate has consistently fallen over the past 50 years, a trend that is likely to continue.

From a global perspective, we still have a fertility rate that is slightly higher than the replacement level. However, many countries worldwide have fertility rates below the replacement level. In 2010, for example, nearly 50 per cent of the world population had lived in a country with ‘below replacement level fertility’. Economists and sociologists are studying the implications of this trend.

Analysis

In his 1798 theory, Thomas Malthus had arrived at the conclusion that population growth is potentially exponential, while the growth of food supply and other resources is linear. Ultimately, in an overpopulated world, we will run out of resources. In light of this theory, is not a declining birth rate something to be happy about?

As the demographic vis a vis economic situation may differ from region to region, the lowering birth rates will have different implications for individual countries. The immediate impact of falling birth rates may not assume global proportions.

Population size is determined by multiple factors such as total fertile population, a nation’s average life span, immigration and birth rate. Hence, low fertility rates will not reduce the total population size in the short term. The overall population in countries with declining birth rates (and birth rates below replacement levels) will continue to grow for a certain amount of time.

However, as the fertility rate falls (and continues to fall below replacement rate), the population of the younger generation will reduce in size; hence the fertile population will also decrease. The implication of a decrease in the fertile population is a population structure that is set to cause further demographic decline. From an economic point of view, the labour force will reduce, and there will be a more significant burden on the smaller labour force to provide for the larger dependent population (with a larger proportion of unproductive retirees, as is being experienced in Japan). Modern technology will come up with automation to meet the labour shortage, but there are other outcomes that will be difficult to address. For instance, with a falling population, especially the productive one, consumer demand will correspondingly drop, which could fundamentally shrink markets. It is for this reason that the marketplace is now seeing a thrust towards consumption by senior citizens and the elderly.

Granted that the recent fall in birth rates have surprised demographic experts, as they have exceeded all predicted trends. High birth rates are prevalent only in poorer African and Asian nations, and even then, the average birth rate is declining.

In the 1970s and 80s, the world had witnessed a dramatic shift in the global birth rate; some of the major factors that had played a role in this shift was access to contraception and China's one-child policy. The effects of the one-child policy seem to be irreversible today.

China has announced that its birth rates have fallen for the past five years. Beijing is worried about the economic impact that this demographic shift may have on the country's future. Although there are technological advancements, the worry about labour shortages and reduced tax revenue is very valid. Acknowledging this, the CCP had reversed the one-child policy in 2016, allowing people to have two children, and in 2021, extending this to three. However, most Chinese women simply do not want to have children. This is an issue that the CCP is struggling to get around. Last year, the total number of deaths and births were very similar; soon, the Chinese population may decline for the first time since the Great Leap Forward.

Is it possible to reverse a low fertility rate? This depends on the underlying factors which impact fertility. Socio-economic factors affecting fertility include the cost of housing, child care, access to flexible working hours for parents, affordable education, etc. These aspects can be addressed by enabling government policies such as paid maternity and paternity leave or access to affordable medical care and education for all families. Economic fluctuations can also impact the fertility rate of a nation. During times of depression, fertility is more likely to drop. Indeed, this was witnessed all across Eastern Europe in the past.

Other factors that have led to low fertility include access to contraception, higher education rates among women, changes in gender norms and expectations, as well as shifts in the idea of the ideal family. Of course, it goes without saying that most of these are positive changes. There is a connection between higher HDI and lower birth rates. As a result, crafting policy to reverse the fertility rate will be significantly trickier in this context.

Counterpoint

In the short term, countries can mitigate the consequences of low fertility through immigration. In the U.S., the fertility rate is above the replacement level primarily due to migration. Immigration will also help to solve the issue of shrinking populations. This means no labour shortages or reduction in consumers.

However, the same is not a long-term solution because immigrant communities also experience declines in birth rates, and eventually, nations worldwide will start to experience birth rates falling below the replacement rate. Certain experts predict that with technological advancements in artificial intelligence and automation, a reduced working population will not impact the economy or development of a nation.

Another solution that has been suggested is to encourage older people to work and delay access to social security/pension. This will help the government to save money and prolong the economic contribution made by a person during his/her lifetime.

Assessment

- For a very long time, experts were mostly concerned about the adverse impact of overpopulation. Today, however, the issue has taken a 360-degree turn, with half the world preoccupied with low birth rates. From a national perspective, such low birth rates can lead to a future where the working population and consumer market shrink, leading to devastating consequences.

- Measures such as promoting immigration, providing better access to child care or encouraging senior citizens to work are only short-term solutions. Demographic experts have to work out a better formula that balances the requirements of a productive labour force with the need to reduce the strain on earth's resources from its teeming millions.

- Technological advancements like automation and AI may offer more promising solutions. However, we cannot truly predict the social consequences of these technologies, especially with respect to disruptions in the labour market.

Comments