A Debt-strapped China?

November 22, 2021 | Expert Insights

Evergrande, one of the largest companies in China, is the world’s most indebted property developer (with over 300 billion dollars of debt). A company that had reached the status of "too big to fail" is now on the brink of collapse. If this happens, it could be devastating for the Chinese economy and cause ripple effects worldwide. However, the country’s financial pains do not just end with Evergrande.

Background

Evergrande is a real estate developer that was founded in 1996. Its current situation is rooted in how the Chinese government liberalised the country back in 1978. When the economy was liberalised, the government held on to what is considered strategic industries. It completely decentralised other parts of the economy that it did not perceive as strategic; this was known as bifurcated capitalism. A large part of the Chinese economy was decentralised to the local level. A consequence of this decentralisation was that the required regulatory structures were missing for many sectors of the economy.

Currently, Evergrande is facing two major issues. Firstly, the Central government has intervened and is regulating bad borrowing habits. This is forcing the company to sell its empire to raise money. Secondly, the Chinese housing market is finally slowing down, contributing to an overall slowdown in the Chinese economy.

Analysis

Although the Evergrande issue has dominated global headlines, it is nothing more than the tip of the iceberg when it comes to China’s debt issues. Like Evergrande, dozens of Chinese developers have bet big on the country’s booming infrastructure. These developers had taken out loans with hefty interest rates and believed that the sales of apartments (which were yet to be made) would be enough to repay all the debt.

Regulators tolerated these risky lending practices because of how developers had helped generate vast amounts of property wealth. Local governments in China had relied on land sales to make revenue. About 40 per cent of local government revenue had come from these land sales. This had only encouraged aggressive sales policies and aided developers to take on massive debts. In total, China’s developers have mounted about 5 trillion dollars in debt. In China, the idea that real estate will deliver income backed by the government is an idea that is as old as the Chinese housing market.

Real estate drives more than 25 per cent of economic output in China. Between 2011 to 2018, real estate investments accounted for 12-15 per cent of the GDP. Once the related property market activity is added to the Chinese numbers, the proportion of GDP becomes closer to 30 per cent.

President Xi has clearly had enough of the sector’s excesses. Xi’s mantra is “homes are for living, not for speculation”. In order to truly stop the speculators, President Xi will have to change the ‘state capitalist’ system, in which local governments are hitting growth targets set by the central government by pumping up their real estate markets.

Covid-19 has brought an overall economic slowdown in China, and property purchases have started to get dragged down. The government has also been implementing policies to curb speculative investments. Certain policies have regulated how many properties individuals can buy. For example, only married couples can own two homes. Government policies are also trying to target the supply side. The “three red lines” policy is a case in point. It refers to three strict caps placed on the ratio of debt a property developer can hold in relation to its assets, equity, and cash on hand. President Xi is yet to fully implement a property tax due to backlash from local governments and the middle class. However, these solutions are simply made to deal with excesses and not to change the system.

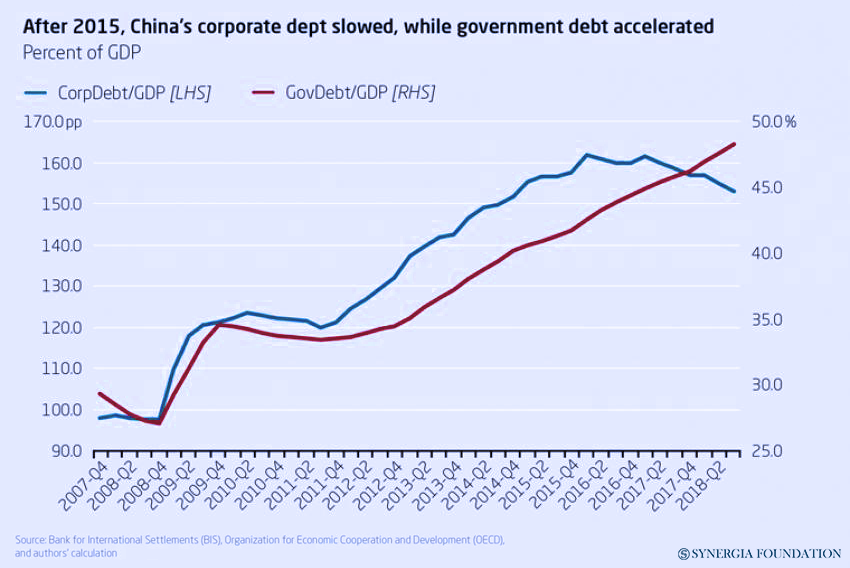

Beyond the housing market, China should be concerned with its debt. The debt has grown drastically over the past decade. In the third quarter of 2020, China's debt was 290 per cent of its GDP. Unlike countries like the U.S. or Japan, most of China's debt is held by corporate sectors (over 160 per cent of GDP). Beijing has recognised this as a threat to its economic security.

Counterpoint

The way the Chinese real estate market operates is very different from the West; this could limit the impact of a bubble bursting. According to Xiaobing Wang, a senior lecturer in the economics of China at the UK's University of Manchester, a crash would negatively impact peoples’ livelihoods; however, the widespread shock to the financial system would be contained. According to Wang, this is because more middle-class Chinese have much higher savings when compared to the West. Down payments in China are 40 per cent compared to just 3-6 per cent in the U.S. Hence the banking system would be able to survive a drop in property prices along with defaults.

Assessment:

- China’s housing market is in a bubble created through excessive speculation. It remains to be seen if the government’s actions will be able to contain the ripple effects when this bubble bursts. Long considered as an engine of growth, the property market is long due for an overhaul before it delivers a fatal blow to the economy.

- From a long-term perspective, China cannot continue to rely so heavily on infrastructure projects to push its economic growth. As the debt burden increases, local governments need to be urged to stop blindly expanding infrastructure projects.

- It would be interesting to note how China is going to balance out its domestic economics with its ambitious and much-vaunted infrastructure outreach through the Belt & Road Initiative. Those who have staked their future in the BRI will be watching with a great deal of anxiety.

Comments