Dam(n) Reality

April 14, 2021 | Expert Insights

In October 1962, during the dedication ceremony of the Bhakra Nangal Dam, Prime Minister Nehru called it “[…} a Temple or a Gurdwara or a Mosque, it inspires our admiration and reverence". Thus was born the phrase, ‘temples of modern India.’

In fact, at this low point in India’s history, the dam was a source of immense national pride, being the only dam in Asia capable of generating 1500 MW power.

Large dams have always caught the public imagination the world over as symbols of national achievements. The last century was a century of ‘large dam revolution.’ harnessing the major river systems in the world. However, swept away in the euphoria of creating these manmade wonders, few questioned their long term sustainability and impact on the environment.

The era of colossal dams peaked in the 1970s, with hundreds built in North America, Europe and Asia. By throttling turbulent rives while producing cheap electricity and watering millions of acres of parched farmland, they re-drafted demographics and national economics. Every emerging nation placed its aspirations for progress on one or more of these behemoths,

CALLING THE COST

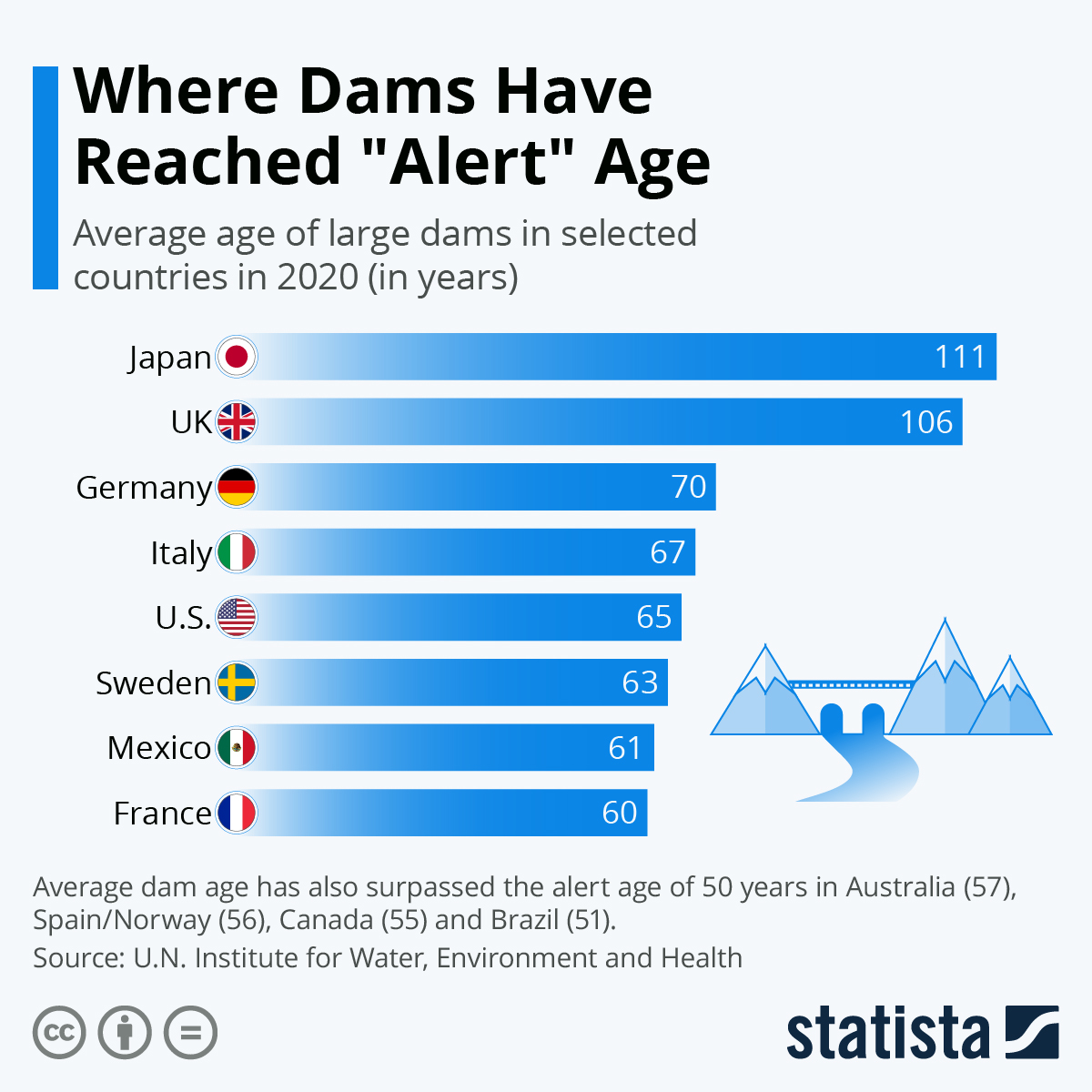

The Institute for Water, Environment and Health at the United Nations University (UNU) points out that thousands of large dams around the world are past the "alert age" of 50, and many are nearing or have crossed their life expectancy of around 100 years.

The average age of operational dams in the United Kingdom is 106, and it is only marginally less in the United States. Over half the large dams in Asia, including hundreds in India, are over 50 years.

Purely in engineering terms to deal with ageing dams, the magnitude of the problem is huge, and the cost of neglect could be astronomical.

Major economies that heavily invested in these gigantic projects are the most affected. In fact, 93 per cent of the world’s large dams are concentrated in 25 countries, with China accounting for nearly 40 per cent. India, too, is amongst these with a long inventory of ageing dams, some built during the British Raj. One of the world’s oldest operational dams is the Kallani dam in the southern Indian state of Tamil Nadu and dates back to the 2nd century AD!

Sedimentation of the reservoir is the primary affliction suffered by old dams. The resultant reduction in water leads to lesser outflow into the network of irrigation canals and fall in electricity generation. Some reports hint at an almost 50 per cent drop in the global reservoir capacity, which has worrying implications for food security. Dredging operations to remove sedimentation of these vast water bodies is economically or technically not an option; the lake will ultimately silt up to its capacity.

Downstream areas of big dams have prospered as flooding became a thing of the past. Now, increasingly, during heavy rains, the overflow from ageing dams is spilling over into these areas, causing death and destruction. With climate change, the problem is feared to get only worse, with flash floods in major rivers expected with greater frequency and little warning.

DECOMMISSIONING

However, decommissioning mega-dams with their associated network of canals, powerhouses, and dependent industry will be no simple task. As per the UNU study, over 85 per cent of U.S. dams are defunct.

The UNU report suggests that decommissioning of unviable or unsafe dams is as important as dam building. It requires an objective and calibrated approach based on empirical evidence and socio-economic realities.

While China and India may feel smug with the knowledge that their dams are relatively young, it is a good time to start their preparations. Indian dams, on average, are just under 50 years old, but many are a legacy of the Raj (and even earlier) and need immediate attention.

The decommissioning process itself is long drawn out and could mean partially removing a dam, fully removing it, or using it for another purpose. The technology exists, but the cost would be prohibitive. The U.S. is contemplating removal of less than 1 per cent of its dams but has launched an invigorated push to maximise the efficiency of existing dams and minimising their adverse environmental impact,

SOCIO-ECONOMIC FACTORS

Over the years, each dam creates its own socio-economic biosphere, which feeds and employs millions. Addressing social realities and agricultural demographics require time and careful planning. However, the value judgement of dams should not come in the way of objective decision making that takes economics and safety as the primary concerns. A good example is an ongoing controversy over the 106-year-old Mullaperiyar dam, which straddles the southern states of Kerala and Tamil Nadu. While Kerala wants a new dam built, Tamil Nadu is against it.

For low-income countries, dams can make or break local economies and shutting down one will almost certainly result in massive economic consequences.

There is a global move away from the construction of large dams, and this means that the way to compensate a decommissioned large dam will not necessarily mean building another. In fact, management of these structures could open a new arena for research and could well be the major challenge in the coming decade.

Assessments

- The time has come to review the economic and environmental feasibility of continuing with these dams and plan their safe decommissioning. Though the threat may not seem immediate in many cases, the fact that it will take years to plan a strategy and execute it demands that the issue is taken up and studied carefully.

- Therefore, countries like India may have to start evolving a long-term road map for their water reservoir and dam economics.

- Ageing water storage infrastructure needs to be addressed as a global issue, and countries without the financial resources or ability to find alternative solutions need to be supported for the larger good. For global application, decommissioning requires a collective sharing of experience and pitfalls in managing ageing dams.

Comments