The Curse of the Magic Metal

May 23, 2021 | Expert Insights

In the thick of the pandemic last year, TESLA used its much-hyped 'Battery Day' to make several announcements, the principal one being the introduction of a new battery technology, free of cobalt. This was underscored by Panasonic, their battery supplier, who claimed that they were on the verge of replacing existing Electrical Vehicle (EV) batteries with cobalt-free ones.

While these announcements brought some solace to activists fighting the unregulated cobalt mining in underdeveloped countries at a great human cost, the market itself showed no sign of abating. In the first few months of this year, cobalt prices have spiralled by over 55 per cent, indicative of galloping demands.

THE LURKING DARKNESS

When John Goodenough invented the lithium-ion rechargeable battery in 1980, using cobalt made in his own laboratory, he never would have realised the geopolitical tremors he would trigger. An energy-dense metal, cobalt is an ideal ingredient in compact battery packs that produce a great deal of power in restricted spaces.

Unsurprisingly, over the last two years, the price of cobalt has quadrupled. The future holds even greater promise as once EVs become commonplace, towards the 2030s, they will require nearly 1000 times more cobalt than smartphones.

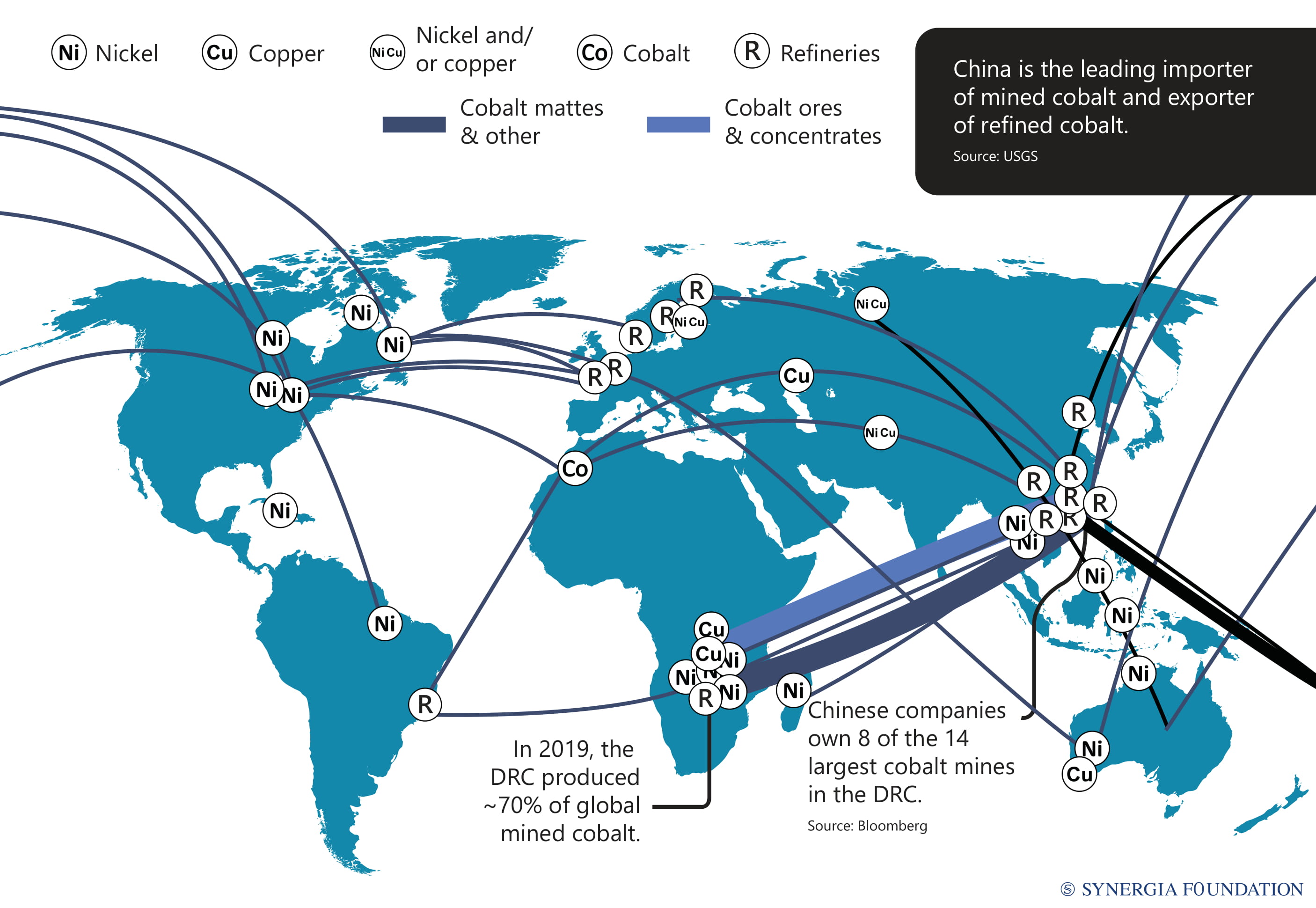

While cobalt can be produced in a lab from nickel and copper, it also exists on its own in the earth's crust. Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), one of Africa's poorest country, produces over 60 per cent of the world's cobalt and has vast reserves.

But all this has come at a darker cost – human rights violations, exploitation of children and environmental degradation. It is the new “Blood Diamond” of Africa.

As early as 2016, Amnesty International had raised a report on the unethical mining practices that led to a new international mining code, raising royalties for cobalt in DRC from 2 to 10 per cent. Then in 2019, a landmark court case was filed against Apple, Google, Dell, Microsoft and Tesla in Washington DC by a human rights firm International Rights Advocate, on the behalf of Congolese families whose children have been forced into slave-like conditions in cobalt mines. These mines are an essential part of the supply chains of the Tech Giants. Plaintiffs named Zhejiang Huayou Cobal, a major Chinese company, as the owner of the said mines.

Artisanry mining in which children work in narrow and deep tunnels, to bring back the bluish-green mineral is rampant. They risk their lives for as low as 2 US$ a day, while thousands have been buried alive in roof collapses. A much larger number of women and children, who are employed to clean the mineral from copper and nickel, suffer from irreversible poisoning.

CANT IT BE REPLACED?

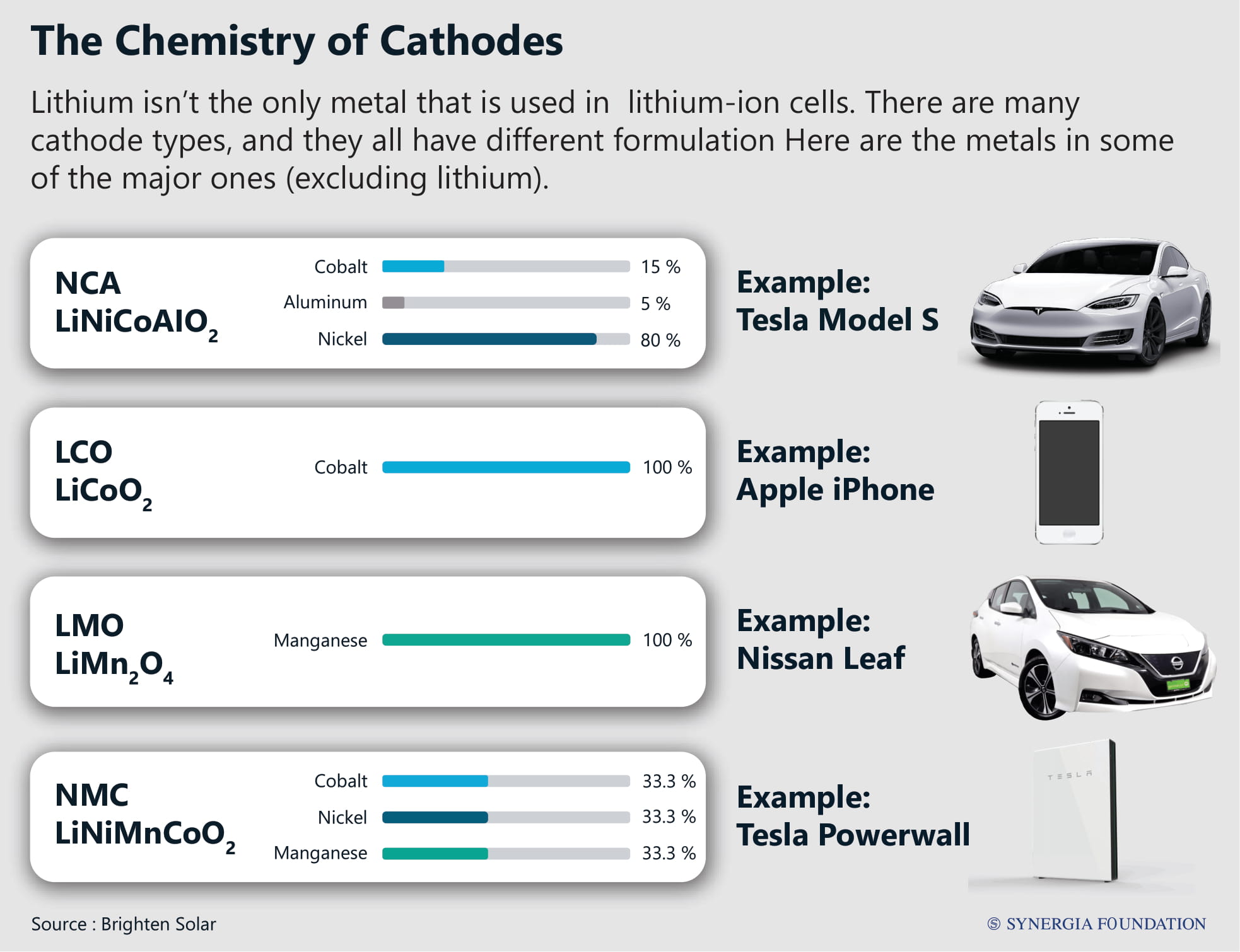

Cobalt gives a longer life cycle to batteries. This is a critical factor for the success of EVs as the market standard for them stipulates an eight-year warranty to retain 80 per cent of the original capacity of the battery.

There is a safety issue involved too. It may be recollected that a few years ago, some models of Samsung Note were banned from flights as their batteries tended to ignite. Even today, power banks with lithium batteries cannot be put in checked-in baggage. To save cost, if manufacturers reduce cobalt in favour of nickel, the cells tend to overheat.

It is feasible to do away with cobalt and use alternatives. However, these are expensive, and big corporations do not want to shell out big bucks, especially if they can get away with cheaper supplies at throwaway prices.

CHANGE IS INEVITABLE

However, pure business sense demands tech companies to avoid paying big bucks for cobalt and disassociate themselves from these atrocities that harm their brand name. Circumstances will ultimately force them to cut down on the amount of cobalt their batteries use.

A new line of research is looking at manganese and iron as layers in batteries instead of cobalt. These are already in use in some devices but do not yet have the same energy density as nickel or cobalt.

Yet another option to bring down the demand for nickel and cobalt is via recycling. However, the long-life cycle of lithium-ion batteries means that by the time there is a demand for replacement of existing ones, after almost a decade, there will be recycled metals available.

Some researchers are looking at solid-state batteries, which, although they need lithium, can do without cobalt. Reportedly, BMW, Toyota and Honda are investing in this technology. However, it is unlikely to be made commercially available before 2025.

In a bid to erase the negative image of cobalt mining, Apple and Samsung are participating in the Responsible Cobalt Initiative, which pledges to deal comprehensively with the environmental and social consequences of their cobalt supply chain. In fact, as per Apple, they have started buying cobalt directly from miners to ensure the workplace standards are met.

GEOPOLITICAL RIVALRY FOR RARE METALS

New technological applications have transformed rare earths and minerals into coveted inputs. Major Powers like China see them as strategic assets and are investing in them accordingly. Cobalt and lithium, although not rare earths, are also mined in a few geographical locations, and are fast becoming indispensable for high tech manufacturing. This resource competition will only become more pronounced in years to come.

China dominates the world in this industry. In 2018, it had constituted a 35 member Union of Mining Companies bolstered by Chinese capital, and with the acquiescence of the DRC regime. China is the leading supplier and consumer of cobalt and has 90 per cent of the global capacity to refine the metal.

In fact, Chinese companies have invested heavily in Congo and control over 40 per cent of the cobalt mining capacity in the African nation. An EU report projected that by the end of this year, lithium-ion battery manufacturing capacity would top 400 GWh, with China accounting for 70 per cent of the installed capacity. This means that China alone would require 80,000 tonnes of cobalt supply.

Also, electric vehicles themselves are only a part of the problem. Batteries used in other devices ranging from cell phones to laptops remain heavily dependent on cobalt. All this lends to projections that the demand for cobalt is estimated to grow four-fold in the next decade. Uses for cobalt are also not restricted to batteries, and the mineral in its radioactive form is even used in the treatment of cancer.

Assessment

- There is a human cost of reducing the demand for cobalt as it would impact almost 85 per cent of Congolese exports, leaving a war-torn country further devastated. Artisanal miners, who lie at the bottom of the cobalt pile, already victims of power and tribal struggles, will only suffer even greater from unemployment.

- This underlines the need for a multi-pronged strategy that addresses the issue of political stability, livelihood, and regulatory conditions for artisanal mining. It is equally important to address exploitative industrial mining and ensure that greed for the mineral does not have disastrous economic, environmental, and social conditions in the republic.

- Ultimately, the humanitarian crisis is buried deep in the demand and supply dynamics for minerals, and this issue may not be restricted to cobalt or Congo. Given the global power dynamics involving China, bringing in a change to Congo and its cobalt realities may not be easy.

Comments