China legalises Uyghur internment camps

October 13, 2018 | Expert Insights

Amid heightened international criticism, Chinese authorities have legitimised the use of internment camps where up to a million Uyghur Muslims are being held.

Background

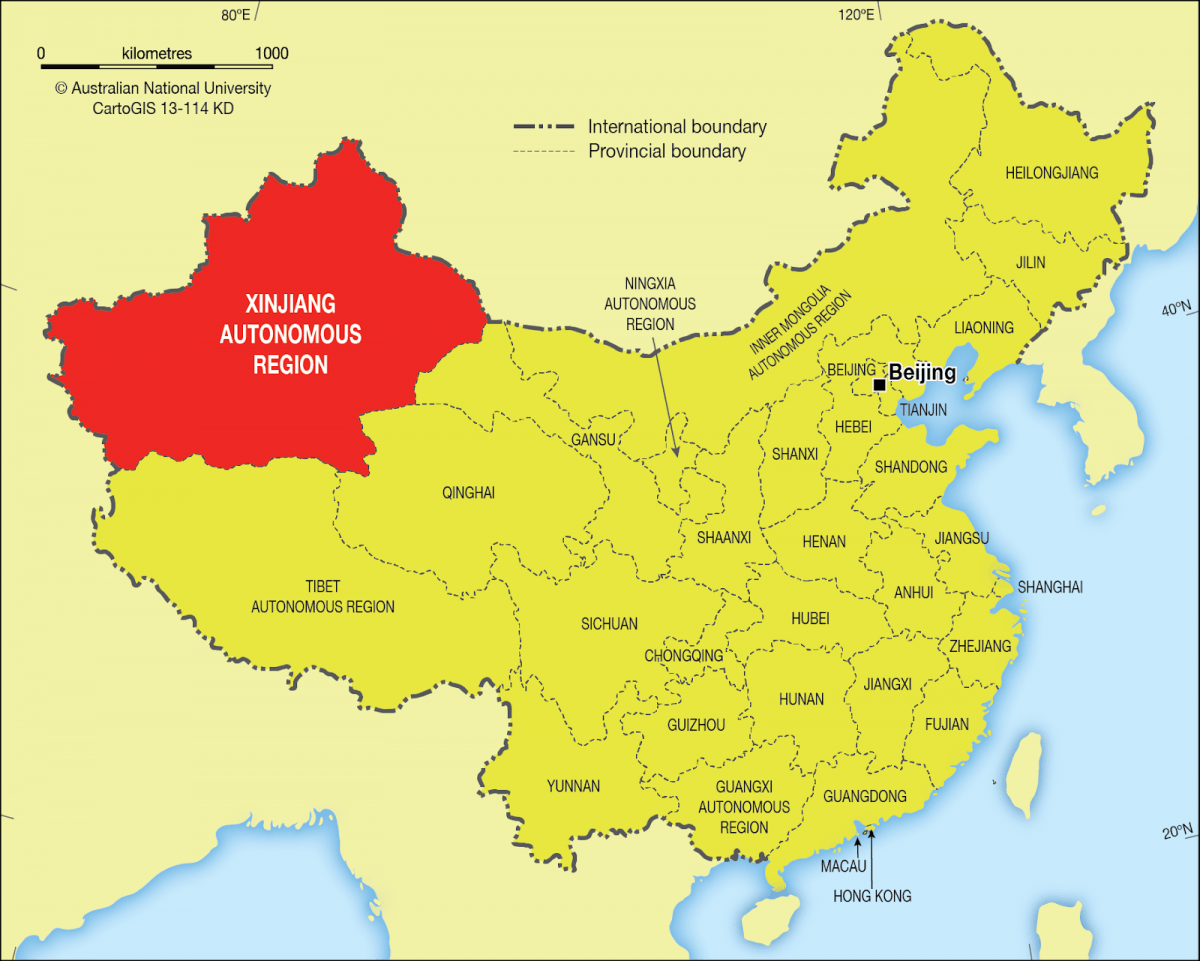

Beijing has detained close to a million Uighurs, an ethnic Muslim population of China’s Western Xinjiang Province. The Uighurs are predominantly Muslims and have regarded themselves as culturally and ethnically close to Central Asian nations. They practice Islam in a mostly atheist country and have inhabited the area since the time of Genghis Khan.

It is believed that the ethnic violence between the Uighur Muslims and the Han Chinese have led to Uighur detention in internment camps. The ethnic tensions were caused by the difference in economic and cultural factors between the communities. The Han Chinese are said to be given the best jobs, and the majority do well economically, thus fuelling resentment among Uighurs.

China has been accused of intensifying the crackdown on the Uighurs after a street protest in the 1990s as well as in the run-up for the Beijing Olympics in 2008. By 2009, this escalated with large-scale rioting in Urumqi. According to officials, 200 people were killed during the unrest, and most of them were Han Chinese.

The government calls these internment camps as “political re-education camps”. There exist credible reports of torture and death among prisoners in the camps. The Chinese government says it is it is fighting “terrorism” and “religious extremism.” However, Uighurs say they are resisting a campaign to crush religious and cultural freedom in China.

Analysis

The regional government of Xinjiang have amended their laws and have legalised the use of internment camps where up to one million Muslims are detained. The government has revised legislation to officially allow “education and training centres” to imprison “people influenced by extremism”.

The updated law has now a legal backing to allow "ideological education, psychological rehabilitation and behavior correction", in addition to teaching the Mandarin language and providing vocational skills in these camps. Furthermore, another clause blocks “refusing public goods like radio and television.” The State media also features programs that praise the developments in the region as well as promote the government’s vision of stability in the territory.

These new rules also ban the behaviour “undermining the implementation” of China’s family planning policies which restrict family size. Besides, last year, authorities had ended an exception that had previously allowed Uighur and other ethnic minorities to have more children than their Han Chinese counterparts. The original legislation announced in 2017 banned the wearing of veils, “extreme speech and behaviour.”

In their submission, to the UN Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination, the Germany-based World Uyghur Congress (WUC) said they estimated at least one million Uyghurs were being held in political indoctrination camps as of July 2018.

The UN panel said it was alarmed by “numerous reports of detention of large numbers of ethnic Uighurs and other Muslim minorities held incommunicado and often for long periods, without being charged or tried, under the pretext of countering terrorism and religious extremism”.

Many foreign media news outlets have documented the disappearance of thousands of Uighurs Muslims in cities across Xinjiang. However, China denies the presence of these internment camps. They say that criminals involved in minor offences are sent to “vocational education and employment training centres”. Chinese representative Hu Lianhe told the UN’s Committee, “The argument that ‘a million Uyghurs are detained in re-education centres’ is completely untrue.”

James Leibold, an expert in China’s ethnic policies at La Trobe University in Melbourne, Australia, said the global criticism of the use of the detention centres have led to the Communist Party in China “scrambling to justify them legally and politically”.

A recent US congressional report has recommended holding individual Chinese officials as accountable for committing “serious human rights abuse”. Although the 2018 annual report’s recommendations by the Congressional-Executive Commission on China are not binding on US authorities, however, under the US Magnitsky Act, they can recommend penalties that include financial sanctions and visa denials if adopted. It said, based on previous reports on the violations in the region, this Uighur detention in China could be “the largest incarceration of an ethnic minority population since World War Two.”

Assessment

Our assessment is that though China has denied the presence of these camps, the recent law to legalise it confirms its existence. We believe that the act of legalising is just a mask to hide the human rights violations that are taking place. In our opinion, this “war against terror” clearly blurs the thin line difference between culture and religion. Besides, further persistence from China could lead to sanctions being imposed by the US despite the impact of the looming trade war. We also feel that a more dedicated effort from international actors with the backing of the UN Human Rights Council could bring some light to the situation in China.

Comments