As India prepares for the aftermath of Cyclone Fani, an important question that needs to be addressed concerns the states governments preparedness to tackle increasingly intense natural calamities. Are the individual states capable of developing local climate change communicators towards climate change adaptation?

Background

Climate resilience can be generally defined as the capacity for a socio-ecological system to absorb stresses and maintain function in the face of external stresses imposed upon it by climate change. It also involves the ability to adapt, reorganize, and evolve into more desirable configurations that improve the sustainability of the system, leaving it better prepared for future climate change impacts.

Hence the building of climate resilience involves the overcoming of macroscopic socioeconomic inequities. The construction of climate resilient communities worldwide will require national and international agencies to address issues of global poverty, industrial development, and food justice. However, this does not mean that actions to improve climate resilience cannot be taken in real time at all levels, although evidence suggests that the most climate-resilient cities and nations have accumulated this resilience through their responses to previous weather-based disasters.

It cannot be denied that the creation of the climate-resilient structures is dependent upon a wide range of social and environmental reforms that are only successfully passed due to the presence of certain socio-political structures such as democracy, activist movements, and decentralization of government.

Building India’s climate resilience

As the world's second most populous country, India is taking action on a number of fronts in order to address poverty, natural resource management, as well as preparing for the inevitable effects of climate change. India has made significant strides in the energy sector and the country is now a global leader in renewable energy. In 2011 India achieved a record $10.3 billion (USD) in clean energy investments, which the country is now using to fund solar, wind, and hydropower projects around the country.

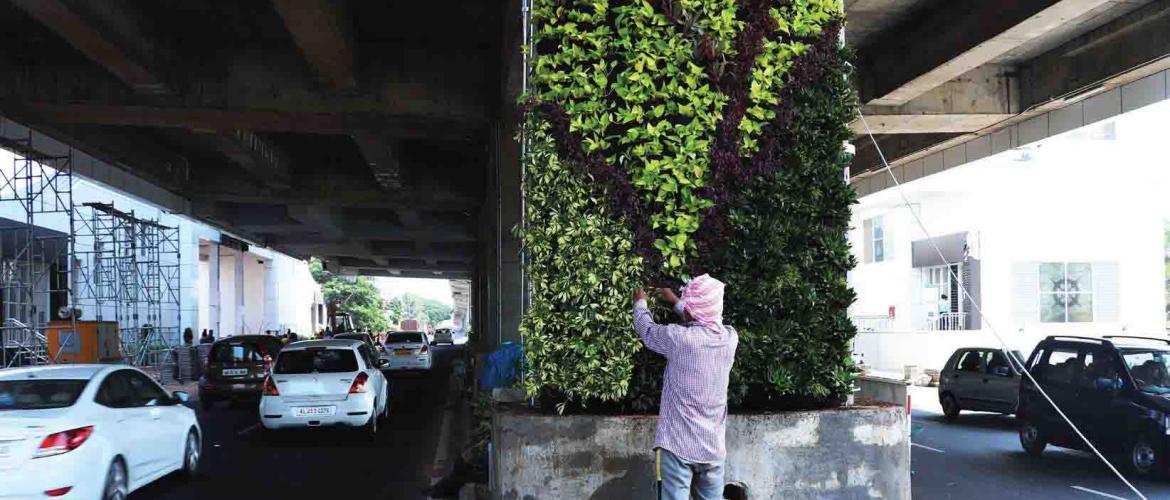

In 2008, India published its National Action Plan on Climate Change (NAPCC), which contains several goals for the country. These goals include but are not limited to: covering one-third of the country with forests and trees, increasing renewable energy supply to 6% of the total energy mix by 2022, and the further maintenance of disaster management. All of the actions work to improve the resiliency of the country as a whole, and this proves to be important because India has an economy closely tied to its natural resource base and climate-sensitive sectors such as agriculture, water, and forestry.

The anticipated future impacts of climate change, identified by the Government of India (GOI) in its Initial National Communication to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) include:

- Decreased snow cover, affecting snow-fed and glacial systems such as the Ganges and Brahmaputra; 70% of the summer flow of the Ganges comes from snowmelt;

- Erratic monsoons with serious effects on rain-fed agriculture, peninsular rivers, water and power supply;

- Decline in wheat production by 4-5 million tonnes with as little as a 1ºC rise in temperature;

- Rising sea levels causing displacement along one of the most densely populated coastlines in the world and threatening freshwater sources and mangrove ecosystems;

- Increased frequency and intensity of floods; increased vulnerability of people in coastal, arid and semi-arid zones of the country; and

- Over 50% of India’s forests are likely to experience a shift in forest types, adversely impacting associated biodiversity and regional climate dynamics, as well as livelihoods based on forest products.

Assessment

Our assessment is that sectors in India most vulnerable to climate change are water, agriculture, forests, natural ecosystems, coastal zones, health, and energy and infrastructure. We believe India’s new generation of climate change adaptation projects as per the NAPCC directives and missions are mostly in development at the moment. However, a number of adaptation focused projects have been launched recently with donor-support or concessional loans. We also feel that Odisha is a prime model for emulation, which is currently recovering from the strongest cyclone to hit the state since the early 2000s. Last year’s floods in Kerala and the preceding floods in Tamil Nadu should serve as a reminder of the steep price of inaction against climate change.